|

By Kathryn Sadakierski Throughout my academic career, it seemed that everyone had different visions of what I should become. Some teachers saw me as a future doctor or lawyer; others encouraged me to pursue studies in the social sciences, education, business, or psychology; another suggested that I simply focus my energy on writing. Imagining myself following these paths, I was overwhelmed by the vast array of possibilities and variables. How would my life change if I chose one over the other? I felt torn, knowing I couldn’t do everything, that I had to define my own dream, my own way forward, amidst so many conflicting views of my calling. Having worked with young children in early childhood and elementary school settings as an assistant teacher, I’ve come to realize a vocation broader than any single career: that of a spiritual mother. There is nothing I love more than nurturing and guiding other souls, pouring myself into helping them to grow, and being present for them, sharing the insights God gives me because He knows what they need to heal. Being a spiritual mother involves being a teacher, and the most important thing I can teach is love. In fulfilling my vocation and living my life for God, I draw upon my variegated academic background and wide array of interests to discern how best to teach and nurture a love for learning, for life, and for all that God has created, in others. Beyond imparting specific skills and content knowledge, a spiritual mother fosters faith and empowers others to live it out, finding wonder and inspiration in all of the little miracles that make up daily life so that, moving forward each day, a spirit of hope can be preserved. At one preschool where I worked, by the end of the day, the 13 three-year-old students in the class were loath to wake from their naps, tired and sometimes teary. As I assembled a collection of books at the table and began to read aloud, tears evaporated, weariness forgotten. Like little listeners of the Sermon on the Mount, all of the children gradually walked up, or sat down in a chair beside me, gathering around to hear the narratives. I channeled all my dramatic skill stemming back from the illustrious days of my roles in elementary school plays (perhaps it was apropos that I’d been cast as the queen once!), bringing characters alive with inflection, connecting the stories to the interests of the students, polling them as to what they thought would happen next, pointing out the vibrant details of the illustrations in the picture books. Enraptured, smiling faces ringed the table, laughter brightened the room, and, once one story ended, I was flooded with requests to read another favorite book, turning the pages again, starting a fresh chapter. In this small way, infusing my love into sharing a story (or several), I could comfort and uplift, offering the spiritual equivalent of a hug, a warm and maternal benediction to go forth with peace. I was led to my calling by a spiritual mother herself: St. Therese of Lisieux, the Carmelite nun known for her “Little Way,” a path toward Heaven paved by a sincere heart and given through everything humbly done for the love of Christ and others. St. Therese viewed each task, no matter how seemingly menial, as an opportunity to joyfully serve God, offering everything up for His glory. Her view later inspired St. Teresa of Calcutta’s life work: to “do small things with great love.” Through each experience, small steps building up towards a larger goal over time, great things can be achieved. Just one kind act has the power to convert another soul. Similarly, starting in middle school, the experiences I had with assisting as a counselor at my church’s Bible Camps, and later with teaching children’s catechism classes, all came together to strengthen my understanding of spiritual motherhood, as I learned how one smile, one encouraging word, could make a positive difference for a child. In her autobiographical masterpiece The Story of a Soul, St. Therese teaches spiritual truths through natural symbols that readers can relate to, just as Jesus did in his parables, illustrating the story of her own soul with rich imagery that captures the many blessings God gave her throughout her short, but no less impactful, life. Specifically, St. Therese likens souls to flowers in a garden, all resplendent in their own unique patterns and colors. If the garden were lacking one type of flower, it wouldn’t be the same, since each blossom radiates its own beauty that can never be replicated. Being a spiritual mother means tending to this garden planted by God, cultivating the seeds of His love, helping others bear fruits honoring the Spirit, and reaching out to Him as they bloom. Just as flowers gravitate to the sun, through nurturing others, I strive to direct them toward the eternal light of the Son. Spiritual teachers like St. Therese have shown me through the legacies of their lives that love is the root of every vocation and makes the greatest impact. This is what allows for growth, for gardens to flourish. It’s not only about providing the necessary tools, but about applying them and always caring. When I consider the far-reaching influence of global leaders, I see my own role as quite humble in comparison. How can I make a difference in my corner of the world? But, as saints such as St. Therese and Mother Teresa have taught me, change truly does start in our own backyards. Transformation is a cumulative process. Every part of our life is used to help us realize our calling and to aid others in finding theirs. Each moment is a stepping stone, another stair that can lead us above the limitations of circumstances so that we can be united with God. God hasn’t made any mistakes, hasn’t failed to take anything into account. What we see as small is an integral part of His plan, a thread in a tapestry of interconnected souls. In God’s eyes, every step matters. Cast in this light, helping children tie their shoes and button their coats are small things done with great love, love that doesn’t need to be communicated in words. Just by being their vibrant selves, the children I work with bring me so much happiness. Similarly, Jesus’ humility, compassion, and patience awe me--I love Him for being all that He is. To be in His Presence, whether at Eucharistic Adoration or in the yard watching the light dance across the sky, is everything. To pray, to do whatever He asks, even the ostensibly small tasks of the day, is important, if only because He has asked them. Anything done for Jesus is valuable. I have come to understand more than ever why God calls everyone to be more like children, so pure-hearted and full of life. It is my goal to help them retain their luminosity, to celebrate it, and carry it well into adulthood. Children learn best when treated with love--but then we all do, regardless of age. My work in the classroom inspires me to lead with love outside of the classroom too, as I realize the incredible need for kindness everywhere in the world. I can bring what I have learned from working with children to helping each person I meet, keeping in mind that love is what all of our hearts long for. My calling involves teaching everyone who comes into my life, through the written and spoken word, about God’s love for them. Not all of us may be called to be biological mothers or fathers, but we all can be spiritual parents, bringing new souls into God’s family by shedding light in the ways unique to each of us. In comforting, healing, teaching, writing, and speaking, I aim to point back to God, to instill hope in His mercy. But whichever route I take in expressing my vocation, God’s love is at the root of each little way, each little seedling that can go so far in brightening the garden. Kathryn Sadakierski’s writing has appeared in anthologies, magazines and literary journals around the world, including Agape Review, Critical Read, Edge of Faith, Ekstasis Magazine, enLIVEN Devotionals, New Jersey English Journal, NewPages Blog, Pensive: A Global Journal of Spirituality and the Arts, Refresh Bible Study Magazine, Snapdragon: A Journal of Art and Healing, Today’s American Catholic and elsewhere. In 2020, she was awarded the C. Warren Hollister Non-Fiction Prize. She holds a B.A. and M.S. from Bay Path University.

Consider thanking our contributors by leaving a comment, sharing this post or buying them a book.

1 Comment

By Philip Bulman A 19-year-old pregnant Guatemalan woman died from injuries suffered when she fell trying to climb the U.S. border wall. Medical personnel tried to deliver her baby, but were unsuccessful. March 2020 Now it is too late to greet Mirian by name, too late for her to tell us the name of her unborn child. Unrooted, they left no petals in the sands of sorrow, only nameless tracks. Someday I will cross my final border free of desert dust. I expect Mirian will meet me on that eternal day. All three of us will dance as she chants and sings her baby’s name. Philip Michael Bulman, a native of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, currently lives in Maryland. His poems have appeared in Eastern Structures and Gargoyle.

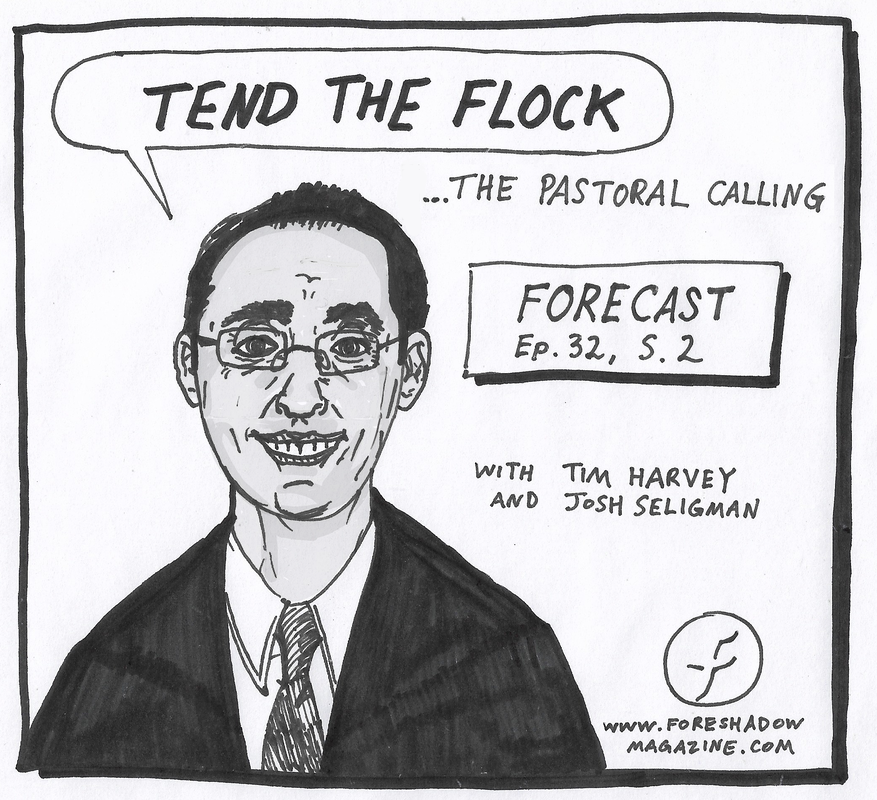

Consider thanking our contributors by leaving a comment, sharing this post or buying them a book. After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google and other platforms. Listen to other Forecasts here. Pastor and writer Tim Harvey speaks with Josh about his calling of being a pastor. After describing how he first became a pastor and what it means to be one in his tradition, he describes supporting the vocations of members of his congregation, including helping people to find their vocations later in life. Then Tim explains how writing is also a calling for him, illustrated by the essay he recently published on Foreshadow, 'And by What We Have Left Undone', which he reads at the end of the episode. Finally, Tim describes the challenges of ministry and where he finds spiritual nourishment. Tim Harvey is the pastor of Oak Grove Church of the Brethren in Roanoke, Virginia.

Tim's other work on Foreshadow: The Comfort that Comes to Those Who Mourn (Non-fiction, May 2021) And by What We Have Left Undone (Non-fiction, June 2022) Consider thanking our contributors by leaving a comment, sharing this post or buying them a book. A short story by Bryant Burroughs Noise surrounds me as if the sun itself were shouting. Ahead of me, bier carriers trudge with a rhythmic crunch on the stony road. Wailing women trail a step behind me. Some are there because it is expected of them, others are mourning my pitiable life, and the honest ones are crying for fear that my fate will fall on them one day. I’ve lived fewer than thirty-five summers, yet I’m walking a fourth time to bury a piece of my heart in the graves on the hillside outside the village. There is no word for a mother who has lost her only child. No word for a woman who has lost everything. I tell myself that my suffering is no greater than the suffering of other mothers and wives for a hundred generations, but such a community brings no comfort. The entanglements of love that make life worth living have all come unthreaded. Outside the village’s south gate, the road before us is straight and gently downhill. A hundred paces ahead, the road curves around the boulder-strewn mountainside and winds toward the fishing villages of Galilee. Opposite this curve is the place of the dead, a rocky hillside pocked with graves. Nain may be a small village, but people have lived here for centuries. In time, most have been borne to this hillside and entombed, their bodies covered with sand and gravel and smaller rocks, then roofed by slabs. It is a spirit-haunted slope. But only one grave matters to me. Up near the crest of the place of the dead, in the section where lie the poorest of this poor village, lie the bones of my two little girls. The first did not survive the womb. The second I held in my arms for only a handful of days, my tears flooding her face as she breathed slowly, slowly, then was still. In that grave, too, is Joel. My Joel. How much we loved each other. With only thirty families in the village, young women have little choice in marriage. Some marry in hope. Most marry to produce sons to labor in the barley fields and the small groves of olive and fig trees. How, then, do two people find a lifetime of love in this place, where few people arrive, and none leave? My Joel proposed as we sat under a fig tree. “Life in Nain is simple,” he said, looking into my eyes. “We sow barley, dig up weeds, harvest barley, trim the trees, and pick olives and figs. What makes it endurable, what makes it worthwhile, is love.” We fit each other. His laugh and arms and strength comforted me and helped me survive when I buried my two little angels in the cold grave high on the hill. In time, I gave him a son: a son who howled from his first breath, a sign of his strong spirit, a spirit that not even a poor farming life could break. We named him Hiphil, “boisterous one.” From the time he stood only to my waist, he worked side by side with Joel in the fields, proud to become just like the man he worshipped. No more children joined us. I longed for a little girl, longed even as my hope unraveled. But we were happy. Then more than hope unraveled. A woman who has lost two little daughters should not have her husband taken away. But God does not think of these matters, and there came a dark day when Joel was carried to the hill of the dead. How long, how long must we kneel and cry to you, until our appeal is heard and you are stirred? Do the ears of God hear no sound? Are the hands of God bound? Are the eyes of God blurred? The only voice I heard in return was my son’s. The son who had smiled at me from my breast when he was seconds old. The son who had idolized and emulated his father, working side-by-side with scythe and olive basket. The son who took my breath away because he had Joel’s eyes and smile. It was my son who helped me step back from all-consuming grief when Joel died. It was Hiphil who worked our fields. It was Hiphil who confronted the village men who promised to help me, but whose leers made clear the price--one I would never pay. I sigh “My son!”, and my memories flee, and reality settles into place. My son has not moved from his funeral bier. All is still and silent. There is no crunching of feet in front of me and no wailing behind me. No one is moving. Could it be that God has stopped time and set things right? No, it can’t be. The crowd at my back comes alive, whispering as if fearful. “Who are these people? “Have so many walked here for this boy’s burial?” “How will we feed them?” “They’re blocking our way!” “Who do they think they are?” “Who is that? Moving a few steps, I peer around Hiphil’s bier. A huge crowd approaches us, a host of men and women and children stretching beyond the road’s curve, people panting and puffing from the uphill climb. Where are they from? Capernaum? But why? Three steps ahead of the crowd is a man whose eyes are fixed on me. His stride is purposeful, as if this is precisely the place he needs to be at this moment: in this lonely town, under this dazzling sky, interrupting this burial. I stand unmoving as he stops directly in front of me. His eyes are fixed only on mine, never looking at the bier or the procession behind me. “Child, don’t cry. Wipe your tears,” he says. The throng swells around us like a stream pushing past two fixed rocks. One of the men behind him complains, “We were in Capernaum yesterday. Climbed here a day and all night. He wouldn’t let us stop for even a moment’s sleep. And as usual, he wouldn’t say why.” Other complaining voices rise from the crowd. “Why have we stopped? Surely he knows we’re thirsty?” “Doesn’t this place have a well?” “We never should have left Capernaum just to follow this nobody from Nazareth.” “Where are we?” “What’s going on up there?” “What’s he saying to that woman?” The man in front of me waits patiently for my words, though I suspect they may not be what he wants. Looking into his eyes, I tell him, “You say ‘don’t cry,’ as if my tears and fears are foolish and will flee at your word.” I wave toward the hill of the dead, a hill I can no longer see as the crowd surges around us. “Look! Up there in cold earth lie the three people I love the most. I called God – I begged, I pleaded. But he was busy elsewhere. Too busy for a nobody.” The man doesn’t release me from his gaze. “You are never outside God’s attention,” he says softly, as if he and I are two friends talking alone under a fig tree. “We circle around God all our lives, pulled and kept close to him. He never loses us.” “I’ve heard that our days and nights are full of angels, running to bring us to the attention of God,” I say. “Love lured me to place my hope in this promise, but love has been overrun. I have no husband and no children to love. Does God know this?” The man now glances at Hiphil’s bier and returns his eyes to mine. “Those you love are not dead. They are more than bones and memories. There is no separation of life into this life followed by that life. There is only life because God is life. One day you will be reunited forever.” Ah! It’s the same trope I’ve heard in the synagogue. It brings no comfort. If they are not alive here, then what good is any talk about being alive one day? I lash out at the man: “I hope, then, that being dead with God is better than being alive with God. I hope he is caring for my husband and three children better than he takes care of me.” Despite my insult, the man’s eyes remain soft. But I feel no urge to make our conversation easy for him. Sweeping a hand behind me, I say, “Look! Here in this place, I’m nothing. Everyone I’ve held dear, God took away from me. I’m left alone. My neighbors are stealing my crops because I have neither husband nor son to defend me. I have no way to resist. I have no one who will keep me safe. I’m without help.” “Child,” he says again, “the Father of all things loves you. He protects widows and orphans and poor.” “Words come easily to you, don’t they?” I retort. “Tell me – does your father have another son he will give me?” A smile joins his kind eyes. “Yes.” I sense he had known from the start this is how it would be. “Dear one,” he continues. “You are right that words and actions should never be apart. But, for your heart’s sake, also remember that hate and hope cannot live together.” I’m empty of words. His gaze has exhausted me. With widening eyes, I watch him half-turn and indicate to the bier carriers that they should lower their load. “No!” I gasp. “Don’t do that to him! Isn’t it enough that he is dead?” Turning to face me again, the man reaches out and touches me, holding my clasped hands in his hand. I feel weak and sink to my knees. He follows me down, keeping my hands in his, kneeling with me on the stony road. My tears rain on his hand as the bier carriers place their burden on the ground and step back. With one hand on mine and the other stretching to the edge of the bier, the man calls over his shoulder, “Hiphil, young man of such tears, I say to you, rise!” Time and sound stop. No one in the crowd moves. All eyes are fixed on the bier. I half-hear a soft rustle, so whispery that it seems to come from the far back of my soul. Despite its softness, it demands attention. I sense that something is being knit together on the bier, as if unraveled threads are weaving together for reuse. Then my son moves. He is moving! He sits up and looks around, as if the part of him that had been unraveled is now whole. The eyes that were Joel’s pinpoint me, and the smile that was Joel’s flashes into my heart. Hiphil is alive! Hundreds of shocked people inhale simultaneously. Those standing nearest the bier fall back in wondrous fear, clutching their hearts or faces or someone’s arm. Then everyone begins shouting or crying, some jumping and others kneeling. This little village, a day’s walk from anywhere, has never seen such a wonder. Even as their cries swirl all around me, I am too weak to rise from the stony road. I watch as the man who had been holding my hands rises, takes my son’s hand, and helps him stand. And into my arms, my son runs! Into my arms! Just as he had run as a child when he and his father returned at dusk from working in the fields. My tears and joy and arms envelop him. “Mother,” he whispers, “I’m here. I’m home.” “Hiphil, my son, my son!” I cry, rocking with him in my arms. It’s not a dream! My son is back! And my heart whispers, “Thank you, God.” The crowd’s celebration resounds off the sky and hills and village gate and hill of the dead. “Surely God has visited us!” they cry. “Surely God has come near!” “Yes, he has,” I cry as the man walks away through the jubilant crowd. “Yes, he has.” Bryant Burroughs is a writer and lives with his wife Ruth in Upstate South Carolina with their three cats. His work has appeared in online sites such as Faith, Hope and Fiction and his blog Guide for the Mostly Perplexed.

Consider thanking our contributors by leaving a comment, sharing this post or buying them a book. After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google and other platforms. Listen to other Forecasts here. Will and Josh continue to map an understanding of calling by reviewing the podcast season thus far. After answering a listener's question about finding one's calling later in life (including a response from Jeff Compton-Nelson), they develop their model of vocation, examine the relationship between vocation and career, discuss what it means to 'put God first', unpack the parable of the talents and explore the priesthood of all believers and the relationship between ordained and non-ordained Christians. Will and Josh are co-hosts of Forecast.

Consider thanking our contributors by leaving a comment, sharing this post or buying them a book. By Emma Winchell Would that my accumulations Reach the height of expectation That they would murmur in the cosmos With the rippling constellations Yet every accolade evaporates into—a breath Or curves into the etching of my marble epitaph Emma is a writer for the Literary Practicum at the Moody Bible Institute. Her work has been published in Thin Space Art & Theology Journal and Ekstasis, the creative journal of Christianity Today. You can read more of her poetry here.

Consider thanking our contributors by leaving a comment, sharing this post or buying them a book. |

Categories

All

ForecastSupport UsArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed