|

By Michael Stalcup after Charles Spurgeon I know not where I go, but know with whom I brave these bleak and beauty-broken lands and know that though he leads me through the tomb yet even there my life is in his hands. Like Christ, I cannot see around the bend of death except believe the Father’s call and pour my life out, trusting him to mend this tattered soul so ravaged by the Fall-- for all the paths of God will end in pure unmingled good to every heir of grace, and though the world would with its fires lure, its warmth cannot compare to his embrace. So lead me through the valleys when you must, my Father — only this: help me to trust. -- Author's note: Christ knew the resurrection would follow his self-sacrifice and, similarly, we know that we will rise again at the resurrection. Here I am emphasizing Christ's shared humanity with us. Jesus was fully human as well as fully divine... and so, in a certain sense, he had to go to the cross in faith that God would raise him from the dead. This is a great mystery, of course, but by "I cannot see," I am emphasizing that, although Christ knew he would rise from the dead, Jesus, in his humanity, could not "see" around that bend until he lived through it. Jesus was the firstfruits of the bodily resurrection of all humanity, and in his full humanity, I believe it is well within the realm of orthodox belief to speak of Jesus modeling faithfulness for us who also must follow in faith, knowing of our resurrection--and living toward it--without yet "seeing" it with our eyes. Michael Stalcup is a Thai American missionary living in Bangkok, Thailand. His poems have been published in Commonweal Magazine, Ekstasis Magazine, First Things, Presence, Sojourners Magazine, and elsewhere. He co-teaches Spirit & Scribe, a workshop helping writers to integrate spiritual formation and writing craft. You can find more of his work at michaelstalcup.com.

'I Know Not Where I Go' first appeared in Resolute Magazine. It has been republished here with the author's permission. Michael's other work published on Foreshadow: Sometimes Mercy (Poetry, September 2022) Covenant Prayer (Poetry, September 2022) Lines Last (Poetry, September 2022) Cultivating (Poetry, October 2022)

0 Comments

By Royal Rhodes after Basho conifers nearby make me look up from my book lost in translation I wanted to write to find love with life again here were better words now cherry blossoms that like snow cover Spring boughs show impermanence layered breaths of clouds moved by the arc of a fan become narratives I know I am watched by eyes in a peacock's tail that blink when I move the ink that darkens outlines how my emptiness cannot be contained all that passes here as theatrical backdrop shows and stops my world our isolation helps nature imagine us in our long absence nature was foreign until I swallowed its soul my mistakes teach me Royal Rhodes taught religious studies for almost 40 years. His poems have appeared in various journals, including Ekstasis, Ekphrastic Review, The Seventh Quarry, and The Montreal Review, among others. His poetry and art collaborations have been published with The Catbird [on the Yadkin] Press in North Carolina.

After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google and other platforms. Listen to other Forecasts here. Church musician Matt Bickett explores the roots of his family and wider Appalachian culture through visiting the gravesites of his ancestors in eastern Kentucky. He connects this journey with his theological study of St Gregory of Nyssa, who taught that perfection is possible only through God's grace and requires an ascent into God and at the same time a descent into mystery. Matt describes the contributions Appalachian culture can make for oppressed communities in other locations. Matt Bickett is a church conductor, organist and scholar currently studying in Tübingen, Germany.

Will Shine is a co-host of Forecast. By Adrian David A priest wrestles between vengeance and forgiveness upon hearing a murderer's tragic confession. Turin, Italy – 1995 The church bell rang out as the morning sun arched over the horizon. Standing at the side of the gate, Cesare stubbed out his cigarette and peered up at the tall, white spire adorning the church. He took a deep, pained breath and entered the house of worship. He yearned for the calm within its walls, his tortured soul aching for comfort. The church was empty except for the lone figure of a priest kneeling before the altar. Sunlight penetrated the blues, reds, greens, and yellows of the stained-glass windows, forming the shape of a large dove upon the floor of the nave. Clouds of smoke wafted from candles throughout the sacred space. Cesare dragged his feet up the aisle, passing the polished wooden pews. His chest tightened; his steps faltered. Painful memories flooded in despite his efforts to suppress them. He froze in his tracks, crippled by his swirling thoughts and tortured conscience. He clutched his chest and collapsed into the nearest pew. * * * Giovanni made the sign of the cross and stood. Adjusting his cassock, he turned from the altar and headed to the rectory. He slowed his pace upon seeing a scrawny, forlorn man. The stranger looked out of place in the pristine church. His receding grey hairline, shabby beard, unkempt clothes, and worn-out bag told a story of strife. The wrinkles on his tanned face exuded misery, and the dark circles under his eyes betrayed his distress. Driven by curiosity and his vocation to help, Giovanni approached the lost soul. “Buongiorno. Is everything alright?” The stranger remained frozen, seemingly unaware of what was happening around him. Giovanni leaned against the pew and cleared his throat, drawing the man’s bloodshot eyes to his face. * * * Cesare scanned the bespectacled priest from head to toe. Dressed in an immaculate white cassock, the thirty-something priest had a pleasant, clean-shaven face that radiated calm. “Did you say something, Padre?” Cesare croaked, licking his dry, cracked lips. “I was just checking if you were alright.” The priest smiled. “Have I seen you here before?” “This is my first visit to your church, Padre.” “That’s good to know. It’s only been a couple of months since my ordination and assignment here. Welcome.” The priest extended his hand. “I’m Giovanni.” “Cesare.” He clasped Giovanni’s hand in his own, offering a feeble handshake. “If you don’t mind me asking,” Giovanni continued. “Your accent… You’re from Sicily, right?” “Si, I… er… just finished my prison sentence.” Cesare bit his lower lip, trying to cloak his guilt. “I came to Turin to meet my cellmate’s family and give them some money. I thought of spending some time in this church before leaving.” With a disarming smile, Giovanni flung his arm around Cesare’s shoulder. “Come, let me show you around.” Incredulous, Cesare stared at the priest, whose friendliness and courtesy didn’t fade even after hearing about his circumstances. “No, Padre.” He shook his head. “I can’t stay here any longer. A sinner like me doesn’t deserve to be here.” “There are no saints or sinners here.” Giovanni’s eyes sparkled. “We are all children of God.” “But…” Cesare raised his palms to his face. “I have done terrible things.” “Would you like to make a confession and clear your mind?” Giovanni adjusted his round glasses. “I am not ready.” Cesare slumped his shoulders and hung his head in shame. “Remember,” the priest said, holding Cesare’s arm. “Whatever you confide in me is between you and God alone.” “I am sorry.” Cesare got to his feet. “I can’t. I have to leave.” Giovanni stood, towering above Cesare. “My seal of confession prohibits me from uttering a word to anyone.” He looked right into his eyes. “Whatever your sins are, I will take them to my grave. A burden shared is a burden halved. Pour out your heart to the Lord, and he will give you rest.” Cesare’s reluctance subsided. The time was ripe to get the burden off his chest. A chance at redemption was knocking at his door, and only a fool would refuse it. He gave a slight nod. “Fine, Padre.” As Giovanni led him to the confessional chamber, Cesare prepared to spill the emotions he had repressed for many years. * * * A grille separated the two halves of the wooden confessional. Lamplight filtered through the grille, scattering bright dots across the walls and illuminating the small metallic crucifix. Giovanni perched on his seat on one side and straightened the purple stole around his neck. He heard Cesare kneel on the other side of the confessional, knees pressing on the cushion. Giovanni turned the pages of his gilded Bible to the third chapter of Colossians. With a gentle voice, he put his finger to the page and tracked as he read the passage: “Bear with one another and, if anyone has a complaint against another, forgive each other; just as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive.” He brought his ear closer to the grille, ready to listen to Cesare’s sins. Cesare said faintly, “Bless me, Padre, for I have sinned.” “How long has it been since your last confession?” “Years. Decades. I don’t know. The last time I made a confession was when I was young.” “What happened after that?” “Life turned miserable. My babbo left our family for another woman. This broke my mamma’s heart, and she became ill.” Cesare choked, his voice breaking. “Everything changed after she died. I ran away from my home and started doing all kinds of dirty jobs to survive — selling drugs, counterfeiting banknotes, pimping out whores. Out of desperation, I indulged in all kinds of evils. Before long, I targeted rich families and robbed their houses while they were away. “That was when…” He paused and groaned. “I did a terrible thing. It has haunted me for the past fifteen years. A memory I can’t escape.” Giovanni leaned forward, listening intently. This wasn’t the first crime to be confessed to him. He had been taught not to be affected by the confessions of his congregation, ensuring he didn’t react to even the worst of transgressions. It was not his place to judge; only God had the right to do that. Giovanni said in a soothing tone, “Do not fear. No matter how great your sin is, God is always here to forgive.” Troubled words spilled from Cesare’s mouth. “Fifteen years ago, I was robbing houses in Sicily. I reached the town of Salemi and targeted a vacant mansion. After hearing that the owner was away on vacation, I broke into the house at midnight and hunted for valuables. I didn’t realize my mistake until it was too late. I was in the wrong house... and I wasn’t alone.” Pulse racing, Giovanni furrowed his eyebrows. “As I was breaking the safe open, a man caught me red-handed. I pulled out my knife, only to intimidate him.” Cesare cleared his throat. “He kept fighting me, and the next thing I knew, there was blood everywhere. I stabbed him in the heat of the moment. I swear I didn’t mean to do that. His wife came running up the stairs, carrying a baby. Her eyes bulged when she saw her husband lying dead. I’ll never forget the look on her face. I tried to muffle her screams with my hands, but she bit me. In a fit of rage, I grabbed her throat and strangled her. The baby fell from her arms to the floor. The cries grew louder, and I was afraid of waking the neighbours. I took a pillow from the bed and…” He hit his head against the grille. His voice trembled. “I smothered the baby to death. Even now, I can hear the child crying. It torments me in my nightmares.” Giovanni swallowed, struggling to keep his breath even. A sudden coldness hit him at the core. “I picked up whatever valuables I could lay my hands on and fled the town. I later learned that the murder remained unsolved.” Cesare coughed. “Three years later, I started working for a mob boss, and soon I was arrested for smuggling drugs and imprisoned. Throughout my days in prison, I never stopped regretting my crime in Salemi. I couldn’t sleep at night; I couldn’t eat. Whenever I heard a baby crying, I covered my ears. Whenever I looked into the mirror, I saw a monster.” Giovanni gritted his teeth. Icy tendrils robbed him of action, freezing him in place. He could do nothing but listen, paralyzed with shock. His focus on the confession wavered. A tidal wave of tragic memories washed over him. Fifteen Years Earlier Standing near the phone in his boarding school dormitory, Giovanni excitedly waited to hear the sweet voices of his parents. They called Saturday mornings at ten without fail. They had called him the previous week for his fifteenth birthday. His eagerness was cut short when one of his teachers stepped into the room and beckoned him to follow. “Gio, the headmaster wants to see you.” Giovanni’s stomach twisted at the urgency in his teacher’s voice. According to his classmates, the headmaster only summoned bad students to his office. Giovanni strived to be first in his class, a model student. He aspired to follow in the footsteps of his father — a self-made businessman who worked hard and built his wealth from the ground up to ensure his family’s well-being. Giovanni trailed behind his teacher. What could it be? Why is he calling me? What have I done wrong? On entering the headmaster’s office, a sense of dread enveloped Giovanni. The headmaster paced the length of his office, pausing as soon as he saw him. “Please sit down, Gio. Have some water.” He motioned to the chair and handed him a glass. Giovanni gave him a nervous smile. “You must be wondering why I called you.” The headmaster gestured to the trunks and bags in the corner. “Your teacher packed your belongings. He will accompany you home. From now on, you must be brave. Braver than you think you can be.” Giovanni straightened his round glasses and blinked like a confused owl. The headmaster tapped his shoulder and let out a deep sigh. “You need to go home to Salemi, son. Something terrible has happened.” The glass of water fell to the floor and shattered. Giovanni’s head spun as the headmaster told him of his family’s fates. The walls closed in on him, and he struggled to breathe. A stream of hot tears rolled down his cheeks, blurring the world around him. He collapsed on the floor and fainted. After he recovered consciousness, Giovanni moved as if through a dream. It was a traumatic memory, one that would follow him throughout his lifetime — the parish priest uttering the final prayers as his father, mother, and baby sister were laid to rest in the town cemetery. His sanity was buried alongside them. The darkness of no one left to call family, of being rendered an orphan, engulfed Giovanni. A walking corpse, he was as dead inside as his family was in the ground. The parish priest took Giovanni under his wing and enrolled him in the Don Bosco Seminary. After several years of rigorous study and devout adherence, Giovanni found his calling. Soon, he was ordained a priest. Despite learning to forgive and forget, bitterness still festered within him like a gaping wound. * * * The terrible truth was too much for Giovanni’s soul to bear. The man he long abhorred was seeking absolution. From him. For the merciless killing of his family. The reminder of his family’s death tore at his insides. So many things ran through his mind. If only Cesare hadn’t broken into his house that uneventful day. If only he hadn’t killed his parents. If only his baby sister had survived. His heart hammered in his chest; his knuckles knotted. As a man of God, Giovanni knew what was demanded of him, but his vision was streaked with red. All the pain he’d locked away had culminated into a ticking bomb, waiting to explode. Cesare cried out in anguish. “I want redemption, Padre. Will God have mercy on a wretched sinner like me?” Hate was an ugly thing, and on a priest, doubly so. Fists clenched in fury, Giovanni levelled his gaze on the sharp edge of the metallic crucifix in front of him. He imagined ramming it right into Cesare’s throat, just as the deranged animal had killed his father. The jaws of hate gnawed on Giovanni’s last nerve. The road of retribution led him to the slopes of madness. Revenge was the only thing the raw wound of his heart demanded. He yearned to kill Cesare. To make him suffer a torturous death would be the sweetest wine. Voices inside Giovanni’s head challenged his sanity. His tormented brain screamed with shrill cries. Kill that bastard! Make him pay! No, forgive him. If you kill him, you’d be no different from him. Listen to me! I said, kill him. Do it for your father, your mother, your baby sister. What will that make you? No better than him. You are God’s servant on earth. Forgiveness is for the weak. Monsters like him don’t deserve to live. Spare his soul! Remember, those who live by the sword shall die by the sword. Heaven and hell twisted together in his mind like a storm. The contradicting voices grew louder. Kill him! Forgive him! Regaining his senses, Giovanni took quick, short breaths. He bit his fist, trying to muffle his inner agony. Help me, Lord. He squeezed his eyes shut. His moral compass wavered; the demons pounding in his mind raged. Yet, in all the darkness, Giovanni saw a ray of hope at the end of the tunnel. The hope that love could transcend all. The forgiveness that Christ offered to the world. The grace that redeemed even the worst of sinners, the redeeming grace. It dawned on Giovanni that salvation was not a reward for the righteous; it was a gift for the guilty. Killing Cesare would not bring back his family. His parents would never wish for him to perpetuate the cycle of violence. Retribution would not ultimately bring him peace. Forgiveness was the most fitting thing he could offer to someone who had wounded him. Giovanni took a deep breath and decided to follow his conscience. “God, the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of His Son has reconciled the world to Himself and” — Giovanni gulped down his sobs and brushed his tears — “sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins. Through the ministry of the Church, may God give you pardon and peace, and I absolve you from your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” Cesare rested his head against the grille and feebly muttered, “Amen.” Giovanni bit his lower lip. “The Lord has heard your confession today. For your penance, you must vow to commit your life to one of goodwill and charity. I have forgiven… er…” he stuttered. “God has forgiven your sins. Go forth and spread the mercy He has granted you. Go in peace.” * * * After all these years, the caged bird was set free. At long last. Rising from the kneeler, Cesare crossed himself and left without saying another word. He retraced his steps toward the gate. He heaved a sigh of relief and glanced at his reflection in a nearby puddle. A new man stared back at him. One redeemed from the unforgiving clutches of sin. A man smiling for the first time in decades. A man who was born again. * * * Back in the chamber, Giovanni slammed his fists into his temples. Misery broke through his fragile control. His throat closed in grief. Waves of despair washed over him, drowning him in the dark days of his family’s demise. Deep down, he was sure his parents would be proud of him from above. No matter how much his soul screamed in anguish, he had done the right thing — the difficult thing. Giovanni struggled to his feet and dragged his weary self out of the chamber. He fell to his knees in front of the altar. The candles cast a flickering red glow upon him. With tears in his eyes, Giovanni lifted his gaze toward Christ on His cross. Mercy had triumphed over vengeance; love had overcome hate. Adrian David writes advertisements by day and short fiction by night. His stories explore themes like faith, love, hope and everything in between, from the mundane to the sublime.

By Caroline Liberatore Snow-laden eyelids flickering Shut, then wide, mirror peeking Behold, the purified landscape Cracked earth blanketed, now faultless Lines, absorbing every drop Until dirt-crust lace dissolves A new embellishment, now Let the coming green remember Dross, may too, be vindicated With a festal blanketing Caroline Liberatore is a poet from Cleveland, Ohio. She has also been published in Ekstasis Magazine and Ashbelt Journal.

Caroline's other work on Foreshadow: Library Liturgy (Poetry, February 2022) Ecology (Psalm 84) (Poetry, August 2022) Unearthings (Poetry, September 2022) By D. S. Martin After John Donne's 'Death's Duel' Can we account for our becoming our souls breathed into tiny bodies by divine breath? Did God weave soul into the fabric of your embryo to protect it from being broken? Each response from your tongue when spoken has its beginning on your exhaled breath Every breath rising from our lungs is a gift we lift along with every song we're singing Though soul is far more than the breath we breathe & spirit far more than the soul we receive all three thankfully each an intricate part of the whole Yet when Christ faced death & released unseen all three into the Father's hands (spirit soul & final breath) he knew that's where they'd always been D.S. Martin is Poet-in-Residence at McMaster Divinity College, and Series Editor for the Poiema Poetry Series from Cascade Books. He has written five poetry collections including Angelicus (2021), Ampersand (2018) and Conspiracy of Light: Poems Inspired by the Legacy of C. S. Lewis (2013). He and his wife live in Brampton, Ontario; they have two adult sons.

By Linda McCullough Moore The bad guys came for him His friends all ran away. They crucified him. He came back to life (It’s what God does) He told the lady At the tomb On Easter morning Go tell the guys, And then he Made them breakfast. At rising from the dead To save the world He was pretty good. At resurrecting sins Maybe not so much Linda McCullough Moore is the author of two story collections, a novel, an essay collection and more than 350 shorter published works. She is the winner of the Pushcart Prize, as well as winner and finalist for numerous national awards. Her first story collection was endorsed by Alice Munro, and equally as joyous, she frequently hears from readers who write to say her work makes a difference in their lives. For many years, she has mentored award-winning writers of fiction, poetry and memoir. She is currently completing a novel, Time Out of Mind, and a collection of her poetry. www.lindamcculloughmoore.com

Linda's other work on Foreshadow: The Counting (Poetry, February 2023) Untitled (Poetry, October 2022) A Little Thing I Wrote (Poetry, October 2022) Wait It Out (Poetry, October 2022) Related work on Foreshadow: Planting Forgiveness (Poetry by Eileen R. Kinch, March 2021) By Sandro F. Piedrahita Based on the life of Edith Stein, a German Jewish philosopher and Christian nun martyred in an Auschwitz gas chamber. Read the first part of this story here. -- At some point – Sister Teresa has lost track of the hours – the guards announce that all the passengers will be moved to another train once they reach the city of Breslau, the town where Sister Teresa was born, the town where she went to synagogue with her mother so many years earlier. By then, a group of around sixty Catholic Jews is congregated around her, listening to her speak and joining her in prayer to Our Lady of Sorrows. It seems that all the Catholic Jews of Holland are being deported to Auschwitz, probably more than a thousand. And Sister Teresa thanks her God because He has allowed her to speak to the people in simple terms which they can understand and which somehow make their journey less fraught. She thinks it is analogous to the gift given to Saint Peter and the other apostles on Pentecost, when they were blessed with the ability to speak in tongues. Sister Teresa, the brilliant phenomenologist who has penned complicated philosophical works like Philosophy and Psychology of the Humanities and Finite and Eternal Being, can suddenly explain deep truths about the Faith in words comprehensible even to a child. She reassures them that there is meaning in life, that they are not hopeless, that the Christ is with them always. And in so doing – in preaching hope – she is dissipating her own doubts. She is strengthening herself as much as those around her. “Do not be afraid, little flock,” she tells them, “for it is God’s pleasure to give you the Kingdom.” “Thank you, rebbe,” one of the passengers tells her, probably a Yiddish-speaking German like herself, “for I was on the verge of despair, and you’ve lifted me with your words.” When they arrive at the railroad depot in Breslau, Sister Teresa is filled with ancient memories: the sound of her mother repeating the psalms in her earnest voice at night, playing hide-and-go-seek with her sisters on days off from school, the scent of the mulberry trees in spring. It was a different world, a world now irrevocably gone. Nothing could be more different from the Breslau of her childhood than the Breslau of the present day – the train station where anxious crowds wonder where they will be taken next, the dust-covered children on the verge of being starved, the gaunt faces of old women and young men sharing the same deep, primal and existential fear. And yet Sister Teresa feels an odd delight in being back in Breslau. She is home again, if only for an instant. She is no longer locked up on the train. She can feel the lambent sunlight upon her cheeks and the soft wind that somehow startles her because after so many hours in a stifling train, the breeze has become something strange and unexpected. Then Johannes recognizes her, after all these years, even though she is wearing the habit of a Carmelite. He is a man in his sixties, rotund and obese, dressed in an orange uniform. Sister Teresa assumes he works sweeping the train depot and wonders if that, too, somehow involves him in the great sin committed there. “Edith!” he cries out. “It must be more than twenty-five years since I last saw you. And you’re a nun! I thought you were Jewish.” “I am,” responds Sister Teresa. “But I’m also a professed Catholic nun. I don’t see a contradiction.” “What brings you here? As far as I know, your sisters have left for America. And your mother passed away years ago.” “I’m going East. I’m on my route to death. The train I’ll board will take me to Auschwitz.” “Oh, you’re on one of those trains, huh? I try not to think about it when I see all the folks heading to the camps.” “Try to get another job,” counsels Sister Teresa. “You should do nothing – nothing – to allow others to perpetrate such a crime. Not even sweep the floors for them.” “Listen,” says Johannes. “I think I may be able to help you. There’s a tool shed some sixty feet away where I keep my brooms and other items. You can hide there, and in the night, I can take you to my home. Nobody will suspect it.” “I don’t know,” responds Sister Teresa, suddenly pensive. “What if the guards catch you?” “I’ll smite them with all my fury. I keep a gun in my tool shed. There aren’t that many Nazi guards.” “That wouldn’t be right. Jesus didn’t allow Peter to kill the men who were about to apprehend Him. And my people need me to be with them. To take them by the hand on this horrible journey.” “So you’d rather die?” “I’d rather live. Life is such a precious gift. But I can’t leave those souls alone. I shall be with them as they walk into the gas chambers. Otherwise they might despair and not carry their Cross as willingly as they should.” “Let me at least give you a little food for your journey.” “No, thank you. We accept nothing.” And then the nun bids Johannes adieu and, after finding her sister, boards the train that is to take them on their final leg to Auschwitz. * * * The Gestapo men who arrived at the Carmelite convent in Echt on a Sunday morning in August 1942 were exceedingly polite and professional in their demeanor. They did not come with guns drawn or break down the door. When Mother Superior Carmen responded to their knocks, they informed her in a cool voice that they were there to apprehend two Jews, Edith and Rosa Stein, who were hiding with the nuns. “Why do you want to arrest them?” the nun asked. “They are both devout Christians.” “If your bishops hadn’t meddled, this wouldn’t be necessary,” one of the Germans responded. “But a couple of weeks ago, all your priests preached from their pulpits at all their Masses that the Nazi treatment of the Jews was immoral and ungodly. So the order has been given. All the Jewish converts must be taken to the camps, especially the religious.” “Well, I won’t allow it. This is a house of God. I demand that you immediately depart.” “You don’t seem to understand,” one of the Gestapo officers replied. He spoke in a serene voice, not animated, knowing he was in a position of power. “The Third Reich does not respect nunneries.” “Tell us where they are,” the other officer commanded, speaking in a louder voice. “Otherwise we’ll just arrest each and every one of you. God knows the concentration camps are full of recalcitrant priests and nuns. We’ll take you, too, if you want to join your Jewish sisters.” “They’re in the chapel,” Mother Carmen responded in a tremulous voice. “You’ll find them praying.” The Gestapo men entered the chapel and found Sister Teresa and Rosa kneeling in front of a great crucifix. Sister Teresa was particularly drawn to the representation of Christ on that crucifix: a masculine Christ, a manly Christ, well-muscled and heavily bearded, with a square jaw, thick eyebrows and a sharp nose, not a lovely, quasi-feminine Jesus as in so many other depictions. And Christ was clearly suffering on that crucifix in the convent at Echt. You could see the pain etched on his face, how the thorns punctured his forehead, how his body was bloodied, spent and tyrannized. Sister Teresa felt that crucifixes should make manifest the horror of the Passion, its sheer brutality, to remind the onlookers of the monstrous agony the Christ was willing to endure for the sake of sinners. As her namesake Saint Teresa of Avila said, there is no affliction too difficult to endure when we consider the torments suffered by the Christ on His Cross at Calvary. Sister Teresa had long understood that contemplating the Cross is not for the faint of heart. And she would soon learn how unfathomably painful it is to be crucified on that Cross. The two Gestapo officers violently interrupted the prayers of the two women. One of the men took a hold of Sister Teresa by the shoulders as she was kneeling and asked her point-blank, “Are you Edith Stein, the converted Jew?” “I am,” the nun answered. “And who are you?” Without answering, the man pulled at her by the hair and threw her on the ground, where he proceeded to handcuff her. “You dirty Jew!” he cried out as he kicked her in the stomach. “Soon you will learn you can’t hide by disguising yourself as a Christian.” “You are the one who disguises himself as a Christian,” she retorted from the ground. “You are an enemy of the Cross. Praised be Jesus Christ!” And then she looked at her sister Rosa, cringing in fear as the other officer approached her with a baton in his hand. “Don’t attempt to resist him,” Sister Teresa said. “Come, Rosa, we are going to join our people.” * * * The train arrives at the outskirts of the Auschwitz concentration camp around ten o’clock in the evening, and soon the guards arrive to tell the passengers to disembark. Folks are wary and do not move quickly, afraid of what their new destination portends. Sister Teresa sees people lingering in the compartment, relatives looking at each other with anxious eyes, not knowing what to do. But soon the guards come with their billy clubs and tell the people to move along. Sister Teresa and her sister take their single valise and begin to march with the rest of the crowd to the exit, shuffling along slowly, prodded forward like sheep by the Nazis wielding their batons. Outside there is already a throng, everyone looking at the ground and at the road before them, following orders like automatons. But Sister Teresa sees a young girl – she must not be older than seventeen – clinging to the door of one of the compartments, refusing to move. A young guard seems to be making a lackluster effort to force her to let go of the door, but there is no anger in his face, only something akin to confusion. “I’m not a Jew!” she cries out. “I am not a convert! I was baptized as a child, and I have always been a Christian!” The young guard pulls at her by the arms somewhat reluctantly, but she continues to resist. “Come on,” he pleads. “Otherwise the others will come, and they’ll beat you. It’s only a short walk to the camp.” “I don’t want to go!” she wails. “I am not a Jew! I hate the Jews!” Then another guard approaches. “What is going on?” he asks in a gruff voice. The girls starts to bawl and repeat again and again: “I am not a Jew! I am not a Jew! I am not a Jew!” Sister Teresa quickly moves ahead of the guard and puts her arms around her. “Do not be afraid, child,” she says. “Come with me. We’ll walk together.” “I know what they do to the Jews!” the girl cries out. “It’s not a secret. They beat them, and they kill them! I have heard that they are gassed to death.” “Come,” the nun says gently, and she takes the girl by the hand. “What is your name?” “My name is Anika.” “That name means ‘grace,’” Sister Teresa responds. “Trust in God’s grace. Do you want to say a prayer with me?” The girl, slowly starting to walk forward with the nun, says, “Yes.” “Come, we’ll pray the Te Deum. O Lord, save thy people and bless thine heritage. Govern them and lift them up forever. Day by day we magnify Thee...” And the girl continues. “O Lord, have Mercy upon us. O Lord, let Thy Mercy lighten upon us, as our trust is in Thee…” They all walk to the valley of murder on a gravel road flanked on either side by trees until they reach the bunkers at the concentration camp. It is a long trail, and it takes the men and women more than two hours to arrive. More than five hundred are placed into what seems like a huge cottage or a large hall where they must stand because there simply isn’t enough space to sit or sleep. Not that many would be able to sleep, thinks Sister Teresa. The guards have announced that at six o’clock in the morning, they will be taken to showers where they will be “de-loused,” and many know exactly what that means. Anika instinctively stays close to the fifty-year-old nun that has given her some semblance of hope. Sister Teresa gently caresses her and repeatedly tells her the words that Jesus had so often imparted to His followers and disciples in their moments of crisis and despair: Do not be afraid. Do not be afraid. Do not be afraid. Anika clutches the nun’s hand and asks for reassurance. “Everything is going to be all right, isn’t it, Sister Teresa?” “Yes,” answers the nun, as she presses the girl’s hand to give her comfort. Then Sister Teresa quotes the Hebrew prophet Jeremiah. “For the Lord has great plans for you. Plans for good and not for disaster, to give you a future and a hope.” “So I will not die tomorrow?” Anika asks. “Perhaps that future promised to you by the Lord is in Heaven, my little girl. Don’t worry about tomorrow. Tomorrow will worry about itself. You only need to pray for strength.” At six o’clock in the morning exactly, the Nazi guards appear and open the doors of the bunker, demanding that all the prisoners undress so they can be taken to the “showers.” Sister Teresa thinks it is one final indignity, completely unnecessary, but remembers that the Good Lord was nearly naked, too, when He was on His road to the Cross at Golgotha. The Jews obey the Nazis’ orders without objection or complaint, knowing that any protests would be useless, and they place their clothes on the ground as they begin to follow the guards. Sister Teresa, walking with Anika and Rosa arm-in-arm, heads to the front of the crowd and begins to sing ancient Jewish hymns. Those who follow her soon begin to do the same, and the guards are surprised by the loud, boisterous chants of the doomed Jews heading to their deaths. As they enter the gas chamber, Sister Teresa looks at the frightened girl at her side and tells her in a triumphant voice, “I say to you today, Anika, you will be with me in Paradise.” Sandro Francisco Piedrahita is an American Catholic writer of Peruvian and Ecuadorian descent. Before he turned to writing, he practised law for a number of years. He is Jesuit-educated, and many of his stories have to do with the lives of saints, told through a modern lens. His wife Rosa is a schoolteacher, his son Joaquin teaches English in China and his daughter Sofia is a social worker. For many years, he was an agnostic, but he has returned to the faith. Mr. Piedrahita holds a degree in Comparative Literature from Yale College and a law degree from Harvard Law School.

Sandro's other work on Foreshadow: The Crucifixion of St. Peter (Part 1 of 2; Fiction, August 2022) The Crucifixion of St. Peter (Part 2 of 2; Fiction, August 2022) A World for Abimael Jones (Part 1 of 2); Fiction, March 2023) A World for Abimael Jones (Part 2 of 2); Fiction, March 2023) A Jew and Her Cross (Part 1 of 2; Fiction, April 2023) After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google and other platforms. Listen to other Forecasts here. Will, Jarel and Josh review the first three conversations of the season. In response to the conversation with Ryan Keating, they discuss intentionality and attentiveness in worship and our daily lives. In response to the conversation with Jessica Walters, they discuss being fully human and alive in Christ as the goal of our faith as well as the church's engagement with the arts. In response to the conversation with Roger Belbin, they discuss the strengths and weaknesses of communal participation and how joining communal activities can draw us out of ourselves towards those around us. Note: the quote commonly attributed to St John Chrysostom in this episode may be an interpretation of his Homily 50.4 on the Gospel of Matthew. Will, Jarel and Josh are co-hosts of Forecast.

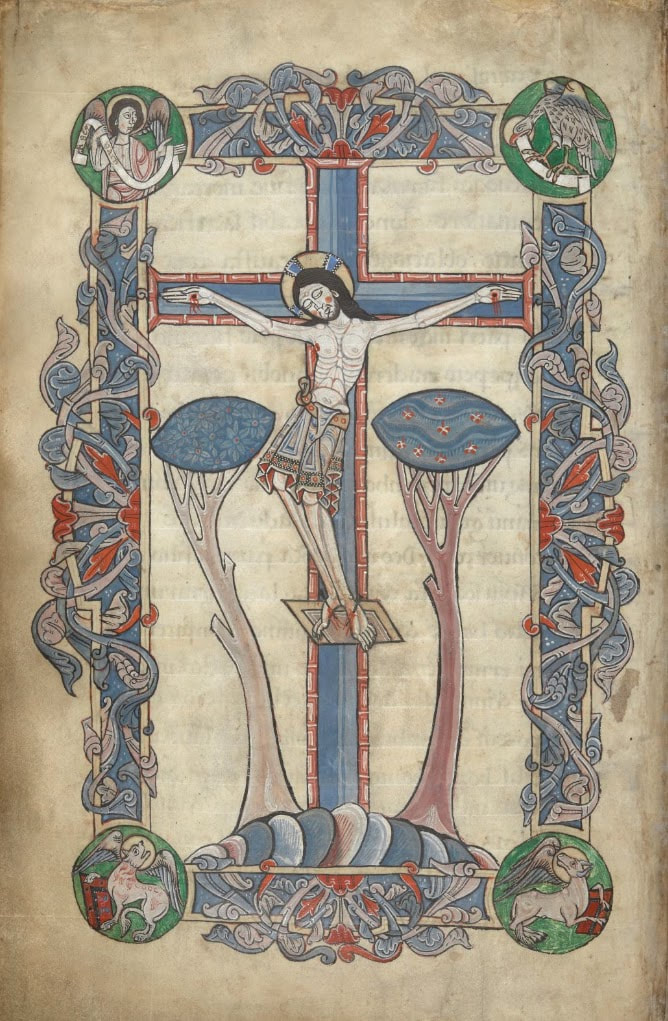

Faithful Cross the Saints rely on, Noble tree beyond compare! Never was there such a scion, Never leaf or flower so rare. Sweet the timber, sweet the iron, Sweet the burden that they bear! Sing, my tongue, in exultation Of our banner and device! Make a solemn proclamation Of a triumph and its price: How the Saviour of creation Conquered by his sacrifice! For, when Adam first offended, Eating that forbidden fruit, Not all hopes of glory ended With the serpent at the root: Broken nature would be mended By a second tree and shoot. Thus the tempter was outwitted By a wisdom deeper still: Remedy and ailment fitted, Means to cure and means to kill; That the world might be acquitted, Christ would do his Father's will. So the Father, out of pity For our self-inflicted doom, Sent him from the heavenly city When the holy time had come: He, the Son and the Almighty, Took our flesh in Mary's womb. Hear a tiny baby crying, Founder of the seas and strands; See his virgin Mother tying Cloth around his feet and hands; Find him in a manger lying Tightly wrapped in swaddling-bands! So he came, the long-expected, Not in glory, not to reign; Only born to be rejected, Choosing hunger, toil and pain, Till the scaffold was erected And the Paschal Lamb was slain. No disgrace was too abhorrent: Nailed and mocked and parched he died; Blood and water, double warrant, Issue from his wounded side, Washing in a mighty torrent Earth and stars and ocean-tide. Lofty timber, smooth your roughness, Flex your boughs for blossoming; Let your fibres lose their toughness, Gently let your tendrils cling; Lay aside your native gruffness, Clasp the body of your King! Noblest tree of all created, Richly jewelled and embossed: Post by Lamb's blood consecrated; Spar that saves the tempest-tossed; Scaffold-beam which, elevated, Carries what the world has cost! Wisdom, power, and adoration To the blessed Trinity For redemption and salvation Through the Paschal Mystery, Now, in every generation, And for all eternity. Amen. Crux Fidelis is an ancient Christian hymn written by Venantius Honorius Clementianus Fortunatus.

|

Categories

All

ForecastSupport UsArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed