|

By Josh Seligman O come, O come Emmanuel and ransom captive Israel that mourns in lonely exile here until the Son of God appear. ('O Come, O Come Emmanuel') It's ironic that this season's wrap-up comes during the weeks leading to Christmas. Until now on Foreshadow, we have shared works about the journeys we make towards God, but during Advent and Christmas, we reflect on the journey that God has made towards us: He came down to earth from heaven who is God and Lord of all ('Once in Royal David's City') Why did God embark on such a pilgrimage? Why did he who was 'in the form of God', in the words of the Apostle Paul, come 'in the likeness of men' (Phil. 2:6, 7)? St. Athanasius answers, 'God became man so that man might become God'. In other words, God came to save us, in the fullest sense of the word (we will explore this subject further next year, God willing). It is only because of God's descent to us that we may ascend to be with God. From nearly the beginning, Christians have believed that because the Word of God became flesh in Jesus Christ, we humans may begin our return to the Paradise that was closed off after Adam and Eve disobeyed God. Christ is the New Adam who fulfills humanity's original task of living in communion with God, a task the first Adam had forsook. In being both God and man, in being both eternal and yet also born of a woman, Christ unites divine nature with human nature. He unites us with God; in him, heaven is fused with earth. So our return to God begins where God's pilgrimage to us ends, at Christmas. In the birth of Jesus, we see a reciprocal blessing similar to that in Psalm 134, the last of the pilgrimage Songs of Ascents. Psalm 134 begins by instructing worshippers to 'Bless the Lord', and it ends with God blessing them: 'The Lord who made heaven and earth bless you from Zion!' Similarly, wrapped in swaddling cloths and lying in a manger, Jesus becomes the blessing offered to God from the Virgin Mary with Joseph, in the company of shepherds and sheep, angels and wise men, on behalf of all humanity and even all of creation. At the same time, Jesus is the blessing given to the world by God, born that man no more may die, born to raise the sons of earth, born to give them second birth. ('Hark the Herald Angels Sing') So in response to offering ourselves and what is ours to God, God blesses us; but we can give only because God has first blessed us. With all this in mind, we end this season with some (but not all) of the strongest works we published this year accompanying each of the Songs of Ascents. May the works we have created and continue to offer join the eternal song of the angels on the night our Saviour was born, and may our lives radiate the peace the angels proclaimed as we come to behold him, in this and every season: Glory to the newborn King! -- Psalm 120: To the Lord in my affliction I cried out, and he heard me

Psalm 121: I lifted my eyes to the mountains; from where shall my help come?

Psalm 122: I was glad when they said to me, 'Let us go into the house of the Lord'

Psalm 124: 'If the Lord had not been with us'...

Psalm 125: Those who trust in the Lord are like Mount Zion

Psalm 126: When the Lord returned the captives of Zion

Psalm 127: Unless the Lord builds the house, those who build it labour in vain Psalm 128: Blessed are all who fear the Lord

Psalm 129: 'Many times they warred against me from my youth'

Psalm 130: Out of the depths I have cried to you

Psalm 131: O Lord, my heart is not exalted Psalm 132: Remember David, O Lord, and all his meekness

Psalm 133: Behold, how good and pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!

Psalm 134: Behold now, bless the Lord Josh Seligman is the founding editor of Foreshadow and a co-host of its podcast, Forecast.

0 Comments

By Joshua Seligman Heaven on earth, we need it now I'm sick of all of this hanging around I'm sick of sorrow, I'm sick of the pain I'm sick of hearing again and again That there's (never) gonna be peace on earth These lyrics come from U2's song 'Peace on Earth', which came out in 2000.* The world was a different place twenty-three years ago, but the lyrics remain timely, expressing a longing for God's peace to come in the face of personal and global evils. Millennia earlier, the Psalmist described a similar longing in different words: O Lord, deliver my soul from unjust lips And from a deceitful tongue.... Woe is me! My sojourning was prolonged; I dwelt with the tents of Kedar. My soul sojourned a long time as a resident alien. With those who hate peace, I was peaceful; When I spoke to them, they made war against me without cause. Psalm 120:2, 5–7 As pastor Eugene Peterson writes about this psalm, 'Such dissatisfaction with the world as it is is preparation for travelling in the way of Christian discipleship. The dissatisfaction, coupled with a longing for peace and truth, can set us on a pilgrim path of wholeness in God.' Such a quest for wholeness in God has motivated pilgrims -- travellers with a spiritual purpose -- for generations. A few hundred years after Christ, the desert fathers and mothers left their possessions and status in single-minded pursuit of God. Their journeys led them into the wilderness to pray and wrestle against evil: in Egypt, they moved to the desert, while in the British Isles, where I live, many of these monks and nuns settled down on wind-swept, desolate islands off the Irish and Scottish coasts. Modern pilgrims still visit these sites today, which in the Celtic Christian tradition are called 'thin places', as visitors often sense there a seemingly thin veil between heaven and earth. One such thin place is Holy Island, Lindisfarne, off the northeast coast of England, where St Aidan established a monastic presence that transformed the region, the effects of which endure to this day. I had the opportunity to visit Holy Island one sunny day last autumn. I was struck by the overwhelming sense of peace that filled me during those few hours of walking on the island and that remained with me long afterwards. But many would say we don't need to travel vast distances to encounter heaven on earth, as powerful as such physical journeys can be. Some Christian traditions say that we can find thin places every week when the church gathers to break bread and worship God. The Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, used by the Orthodox Church, begins with the words 'Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit'. The priest thus announces at the start of the service that the worshipping community is about to embark on a spiritual journey into the heavenly kingdom, joining the worship that is already happening there. 'The liturgy of the Eucharist is best understood as a journey or procession', writes theologian Alexander Schmemann. 'It is the journey of the Church into the dimension of the Kingdom....It is not an escape from the world, rather it is the arrival at a vantage point from which we can see more deeply into the reality of the world.' In other words, worship is an ascent into the presence of God, and this experience transforms our ongoing relationship with the world around and within us. Perhaps the point of visiting a thin place, whether a holy island or a church service, is to absorb its qualities so that we can help make our homes and work places and communities little thin places of their own. Such journeys can also help us identify God's presence wherever we are and wherever we go. To a smaller degree, do we not also make such ascents whenever we step outside ourselves to honour the image of God in the people before us and whenever we open our ears to listen for God's still, small voice? Conversely, if we fail to recognise Christ in others, we fail to make the heavenly ascent. As St John Chrysostom warns, 'Would you do honor to Christ's body? Neglect Him not when naked; do not while here you honour Him with silken garments, neglect Him perishing without of cold and nakedness. For He that said, "This is my body", and by His word confirmed the fact, this same said, "You saw me and hungered, and fed me not"; and, "Inasmuch as you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me."' The ancient Hebrews also understood worship as an ascent. Their primary thin place, the temple in Jerusalem, was on a mountain, so their travels there for annual feast and holy days involved a literal climb. On their ascents, they would sing songs to accompany them. We call these the Songs of Ascents, and they can be found in the Book of Psalms. These fifteen psalms (120 to 134) cover a range of topics, from issues of the human heart to family life to socio-political concerns to blessings for the road. It's as if the songs enabled the pilgrims to bring the entirety of their lives before God in prayer, communally and individually, as they approached the temple, as they prepared for worship. At the same time, I imagine the songs gave them spiritual fuel for the hike. The Songs of Ascents and the pilgrimages for which they have been sung are the focus of Foreshadow this year. The editors and co-hosts look forward to sharing creative writing, podcast conversations and other works that offer personal stories and reflections on the journeys we take, spiritual and physical, in search of heaven on earth and wholeness in God. We hope these works provide courage, insight and inspiration for the path ahead. -- * Although in the original song, the line is 'There's gonna be peace on earth', in a live version, the line is 'There's never gonna be peace on earth'. Joshua Seligman is the founding editor of Foreshadow and a co-host of its podcast, Forecast.

By Josh Seligman Jonah went out and sat down at a place east of the city. Jonah 4:5 In my foreword introducing the season, I reflected on the prophet Jonah, especially how, at one turning point in his life, he reorients his life to God: 'I worship the LORD', he says, accepting responsibility for his actions and offering himself entirely to God. This, I suggested, can serve as a model of how we, too, are called to continually reorient ourselves towards God. (This calling to worship God will be explored more deeply next year.) But there is a second turning point in Jonah's story, and this takes place at the very end. Jonah has (reluctantly) proclaimed God's word to Nineveh; the Ninevites have repented. Mission accomplished! But the story is not over. There is still more work to be done: although Jonah has performed his task, although the Ninevites have turned from their violent ways and although even God seems to have changed his mind, now sparing the Ninevites from destruction, Jonah's heart remains unchanged. Jonah leaves Nineveh and sits down somewhere east of it, '[waiting] to see what would happen to the city' (Jonah 4:5), perhaps hoping that it would be destroyed anyway. Then, through growing a vine to shelter Jonah from the scorching wind and later destroying the vine, God teaches Jonah that, just as Jonah has cared for the vine, so God also cares for Nineveh. The story ends with God's question to Jonah: 'Should I not be concerned about that great city?' (4:11). Here, Jonah is faced with another turning point. Will he remain as he is, angry enough to die, or will he understand the great love and mercy God has for Jonah's enemies, and so live the richer, fuller life that God has for him? Although Jonah has completed the first task God has given him, resulting in the salvation of his enemies, there is a deeper task to which he is called, resulting in his own salvation. He is now called to understand more completely the mystery of God's love, to be transformed so that he might begin to love the people and land he has been sent to save. This second calling of Jonah surprises me because when I think about vocation, I usually think about it in terms of external work people do for God or others. As examples of such work, I can point to the abundance of compelling writing and conversations we have published this year, such as Kathryn Sadakierski's description of serving children as a spiritual mother, Alina Sayre's personal essay on her calling as a writer or my interview with Tim Harvey on tending a congregation as an ordained minister, to name just a few. While such external tasks are important, the ending of Jonah's story suggests that they are only made complete with our inward transformation. In other words, vocation is not only about our deeds but also about our character formation. It's not only about the work we do in the world; it's more fundamentally about the work that God is doing in us, with our cooperation, to change us, heal us and make us whole. When Jesus calls the Apostle Peter to follow him, for example, this calling certainly involves specific tasks he must do, such as strengthening, nourishing and teaching the other disciples. But in order to do these and other things, Peter's heart must first be transformed. Indeed, after Jesus' resurrection and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, we see that Peter develops the courage and power to serve Christ faithfully (this ongoing transformation of Peter's character is expressed wonderfully in Sandro F. Piedrahita's short story 'The Crucifixion of St. Peter'). As Peter would write concerning vocation, such a transformation is nothing less than '[participation] in the divine nature' (2 Peter 1:3–4). Who we are called to become, therefore, are humans ablaze with divinity. The Church has historically understood that such a transformation is the very reason God became incarnate in Jesus Christ. As Church Father Athanasius said, 'God became man that man might become [like] God'. Although this transformation is a gift from God, it requires our engagement. Peter urges his listeners to 'make every effort to add to your faith goodness; and to goodness, knowledge; and to knowledge, self-control; and to self-control, perseverance; and to perseverance, godliness; and to godliness, brotherly kindness; and to brotherly kindness, love' (vv. 5–7) so that our work for Christ does not become 'ineffective or unproductive' (v. 8). In other words, these qualities, the foremost of which is love, are required ingredients for living fully into our calling, enlivening and empowering our activity. Also, we must do all we can, with God's help, to cultivate these qualities. Without this internal work, whatever external work we do is incomplete at best. As the Apostle Paul wrote to the Corinthian Christians, even if we do the holiest and most sacrificial deeds, if we do not have love, we gain nothing (1 Cor. 13:1–3). Our podcast guest Valencio Jackson, for example, has held a variety of different jobs, from engineer to aquatics director to music teacher. But as he describes to Will, he understands his calling as putting God and other people above himself in whatever he is doing, keeping himself open to God's voice. I imagine that, like sunlight shining through several different stained-glass panels at once, such an orientation has enlivened and empowered each of Valencio's roles. Such a disposition, I would argue, is also what God is trying to cultivate in Jonah. The book named after him ends with a question: 'Should I not be concerned about that great city?' (Jonah 4:11). This implies, 'Should you, Jonah, not also be concerned about that great city? Should you not also pray and work for the well-being of the people and animals that live there? Should you not also be transformed so that your heart resembles mine, offering mercy even to your enemies?' As we go about seeking to fulfil the work God has given us to do, may we hear for ourselves God's question to Jonah. May we understand our calling not only in terms of what we do but also who we are becoming -- and may we continually embark on that pilgrimage towards transformation in Christ. -- Thank you to all of our contributors and guests this season! It has been a privilege meeting and working with you all, and the Foreshadow team hope to see more of your work next year. Thank you also to the Foreshadow/Forecast editorial team for their insights and hard work. I've included links to many, but not all, of the work we published this season in the article above based on their relevance to my message. Unfortunately, I was unable to include everyone's work here, but I encourage you to check out all of the writing and conversations from this past season. Next year, our theme will be 'Songs of Ascents: Pilgrimage and Worship'. Stay tuned for a foreword introducing the theme in January 2023. In the meantime, submissions for next year open on 1 December 2022, and look out for bonus material over Advent and Christmas. Josh is the founding editor of Foreshadow and a co-host of its podcast, Forecast.

Please support us by sharing this post or buying us a book. By Josh Seligman After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the music to load. This foreword to Foreshadow 2022 begins with a song about the prophet Jonah (told from the perspective of the vine). This is because Jonah's story illustrates various dimensions of our theme of vocation. Some dimensions are quite obvious. Jonah receives a prophetic call from God to 'Go to the great city of Nineveh and preach against it' (Jonah 1:1). Jonah tries to run away but finds God in pursuit. God also calls the Ninevites to turn from their evil and live fully in God's love and mercy for them (4:11). The song above even suggests that the vine is called is to teach Jonah of God's concern for Nineveh and all life. But the story gives deeper vocational insights. In the middle of Jonah's flight, the sailors ask him who is responsible for the storm. They ask who he is, where he is from and what he does for a living. But rather than identifying himself primarily by his occupation or lineage, Jonah confesses that he is a worshipper of the LORD, who made the sea and land (1:9). Jonah accepts responsibility for the storm due to his disobedience to the God he claims to worship, the God who has power over the world. More deeply, Jonah recognises that he belongs to God: his deepest vocation is to worship the Lord. It is at this point that Jonah realigns his life with God's purposes. The sailors reluctantly throw him into the sea, as he requests, the storm stops and the sailors themselves worship God (1:16). In the belly of the great fish, Jonah continues worshiping God with a psalm (ch. 2). Confident that God will restore him, Jonah recommits himself to God (2:9). In the context of vocation, purpose and identity, we might ask ourselves the same questions the sailors ask Jonah: 'What is your occupation? Where do you come from? What is your country? And of what people are you?' (1:8). How would we respond? Like Jonah, how might identifying ourselves foremost as worshippers of God change our lives? I share the above description of Jonah to give an example of the conversations Foreshadow will be exploring this year. Although I expect we will discuss aspects of vocation beyond worship, prophets and being wrapped up in seaweed for three days, I hope it illustrates the general direction in which we will be heading. I am left dwelling on the image of Jonah in the belly of the fish, offering his life to God. There, Jonah rediscovers his deepest calling. In the words of theologian Alexander Schmemann, '"Homo sapiens," "homo faber" . . . yes, but first of all, "homo adorans." The first, the basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands in the centre of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God.' Jonah in the belly of the fish, the 'centre of the world', becomes a sign and foreshadow of Jesus, the great High Priest, who offered himself to God through the belly of death for three days in order to reunite the world with God. Jesus paves the way, showing us how and empowering us to become fully human, fulfilling God's purposes for us. It is in offering ourselves to God that we receive new life for ourselves and others. The title of our theme this year is 'Called Forth: Vocation and Faith'. This theme organically grows out of the content we shared last year. For example, in 'The Comfort that Comes to Those Who Mourn', Tim Harvey describes some of his challenges and aspirations as a pastor, while in 'A Mother's Loss and the Father's Love', Kelcey Ellis writes about what adopting a foster child has taught her about the fatherhood of God. In our Forecast episode 'Listening Inwardly', Scott Stevens explains how he feels created to compose music, and in 'The Physician's Role Is to Care', Matt Jackson integrates his work as a doctor with his faith. These are just a few examples; you can find all of last year's work on our Contents page. As before, new work will be posted on the Foreshadow website every Monday. Included will be writing and art of a different era (our Foresight series). I invite anyone to contribute to our theme by submitting writing, art or music; you can find submission guidelines here. Regarding Forecast, Will Shine and I are preparing more episodes and interviews that follow our theme. We look forward to launching these soon. In the meantime, you can find our previous episodes here. If you haven't already, I encourage you to sign up to our newsletter. I will aim to send this newsletter out every Monday, as usual, but if I am delayed, especially over the next month or so, this is likely because of the baby that's on the way. Even if I don't send a newsletter on a certain week, I still intend to post new work on the main website every week, so you can check the website regularly for updates. Thank you for reading and supporting Foreshadow. I look forward to journeying with you this year through our exploration of vocation -- whether that involves a trip to Nineveh or faithfully serving God wherever we are. Josh is the founding editor of Foreshadow and a co-host of its podcast, Forecast.

By Josh Seligman What is the kingdom of God like? This is one question Foreshadow sought to address in this past year's theme of pointing to the kingdom of God. (You can read more about the question in the Foreword here.) Over the past year, our authors and contributors have responded to the question through poetry, prose, art, music and conversation. Usually, they have not answered with a direct definition ('The kingdom of God is X') but with a narrative or image, as Jesus often did in his parables ('The kingdom of God is like Y'). Sometimes, our contributors referenced the Beatitudes, the beginning of Jesus' Sermon on the Mount in which he describes the characteristics of people who belong to God's kingdom. So, this review of the past year of Foreshadow features some of our work in relation to the Beatitudes. Of course, there are many more excellent works on Foreshadow; the pieces below have been selected for their strong resonance with this past year's theme and the Beatitudes. To view our other works, you can visit the Contents page here. Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

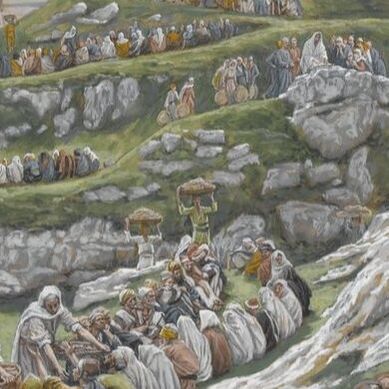

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

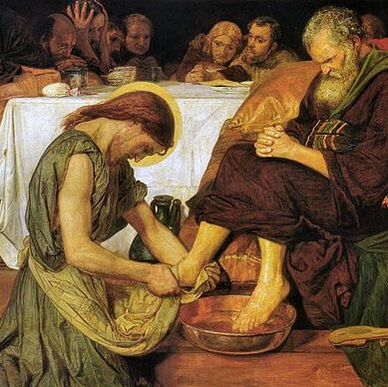

Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Next year, our theme is 'Called Forth: Vocation and Faith'. Submissions are open, so do share with us any work that contributes to the conversation. You can view submission guidelines here. God-willing, I look forward to 'seeing' you early next year, sharing more work that points to the kingdom of God. Josh Seligman is the founding editor of Foreshadow and a co-host of its podcast, Forecast.

After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google, Podomatic, Player FM and Deezer. Listen to other Forecasts here. Jesus said, 'Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.' But in a culture that prizes strength and often overlooks meekness (or gentleness), what is the value of gentleness? This Forecast is an arrangement of writing, music and conversation, some of which have been published on Foreshadow and some elsewhere, connected by their witness to the strength of gentleness. Outline of today's Forecast, including links

Below is an excerpt from the clip with Scott Stevens featured in today's Forecast. It has been lightly edited for clarity and concision. When you suffer from the symptoms of Parkinson’s – the shaking of your limbs, of your digits, your head, your feet, your hand – that’s a fairly fragile and vulnerable thing to experience…When I was thinking about the shakes in terms of music, I started thinking that this needs to be a story that’s very vulnerable and offers some very thin and fragile sounds. Jared, at the very start, said, ‘Scott, I need you to think broken instruments, discarded instruments' – which isn’t to say I broke a piano and lit a guitar on fire or anything – but trying to feature very fragile sounds… Dan’s life followed that arc in a very interesting way in that, as his body became more frail, as it became more susceptible to all kinds of things – even though some might look at that as a decrescendo, the twilight of his life, on his way out, getting quieter – the intentionality with which he lived his life became much more focused, and the things he accomplished – helping establish an orphanage in Rwanda and trying to make reparations, reconciliations with people, trying to be more soft-hearted than he’d been – to me it felt much more like a crescendo, like even as your body’s growing more and more weak, the force and faith and intentionality of your life is growing. Scott Stevens is a composer whose versatility stems from eclectic influences. His music is featured in multiple independent film scores as well as ads for Toyota, Saatchi & Saatchi and Red Bull, among others. Scott holds a Bachelor’s degree in Music Composition from Point Loma Nazarene University and a Master’s degree in Global Music Composition from San Diego State University.

Scott's other work on Foreshadow: Dawn Will Prevail (Music, December 2020) Perspective (Music, January 2021) Listening Inwardly (Interview, April 2021) Josh Seligman is the founding editor of Foreshadow. By Josh Seligman This month marks half a year of Foreshadow’s existence as an online literary magazine. I want to take this occasion to update you on Foreshadow’s emerging identity. I identify three qualities that the magazine aspires towards:

Please do get in touch if you have any questions or comments. Thank you for reading, listening and supporting. With your help, I look forward to seeing what the future has in store. Josh Seligman is the founding editor of Foreshadow and co-host of its podcast, Forecast.

By Josh Seligman 'Ah, but what is the Kingdom of God?'

A relative asked me this question recently when I was describing Foreshadow to her. She is a theologian by profession, but it's a question I suspect most people ask, at least subconsciously, when I tell them that Foreshadow will feature writing that points to the Kingdom of God. My answer to this question, as it involves Foreshadow, is essentially 'Watch this space'. One of my aims is that Foreshadow embodies an answer to this question through its memoir pieces, fiction stories, poems, music and other content. As several of my professors have advised in the craft of creative writing, 'Show, don't tell.' Didn't Jesus himself describe the Kingdom of God through stories and images?

Stories and metaphors have power to teach people about spiritual realities that are difficult, if not impossible, to describe through other means. I'm not saying direct teaching or preaching is ineffective. Jesus did this too, and called his disciples to do the same. It's essential, and it doesn't exclude the use of imagery. Effective sermons, for example, use illustrations to help listeners connect with and understand the message. But many magazines already feature sermons and direct forms of teaching, and many do it well. Not many publications, though, are dedicated to proclaiming the Good News of the Kingdom primarily through art, beauty, music and narrative. Foreshadow seeks to fill this gap. As author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry said, 'If you want to build a ship, don't drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.' I wonder if one of the reasons Jesus told his parables was to teach us to yearn and strive for the Kingdom of God. May Foreshadow continue that work. |

Categories

All

ForecastSupport UsArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed