|

After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google, Podomatic, Player FM and Deezer. Listen to other Forecasts here. Poet and writing teacher Carl Winderl discusses his writing disciplines and the inspiration behind his work. After reading and exploring two poems from his recent book The Gospel According . . . to Mary, he describes his ministry work in Kiev, Ukraine. This is part one of two episodes, the second of which is scheduled to go live next month. Host: Josh Seligman Some links to Carl's poetry - 'kneeling at the Manger' (The Christian Century) - The Gospel According . . . to Mary (Finishing Line Press, 2021) Below are excerpts from today's Forecast about Carl's faith and work. This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and concision. No days off No matter where I go, I write. I write every day, no days off. I'm blessed to be able to do that...What I do, as I've been doing for the last 25, 30 years: the first fruits of my day go to my writing. There's no conflict in my writing between my faith and my art. I feel very blessed, like Michelangelo. We know him as a sculptor, and most of what infused his art was his faith. Everybody knows the David there in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. What a marvellous piece of sculpture, but it's also an impressive piece of faith at work. For me, that's what gets me out of bed in the morning. Even when I was a faculty member, I would try to get after-chapel classes or around-lunchtime classes so that I could stay at home and spend the first three or four hours of the day working on my poetry. My antennae are always up What really infuses my writing is that every day in my writing, I spend time with a variety of texts. It's a process that I started in graduate school. I didn't want to sit down and read three hours of Henry James, so what I would do is I'd read fifteen minutes of Henry James and then read fifteen minutes of Ernest Hemingway, then I would pick and choose and go back and forth to keep my mind alert. Basically, my mind is open. I always keep it open when I'm doing my writing in the morning. I have six or seven texts. This morning I woke up at 5:45, came out of bed at about 6, ate a light breakfast, and came into my writing space. I have right before me seven different texts...I always have a book of poetry...I rotate around back and forth and my antennae are always up. So here I am immersing myself in a variety of texts in dialogue. I have paper in front of me, and when I feel like something's inspiring me, I'll make a note and I'll maybe start a poem, or I'll just keep moving on, and eventually, I'll get an idea from the reservoir that's inside of me. I will do this until about noon. I don't have a set agenda, where I have to start three poems. Some mornings, I start three or four, and some mornings I start one. Today I've only done one so far. And then I also spend some time revising, rereading. I call them 'pep rallies'. I read stuff that I've written before to get me enthused so that I'll know, 'Oh, I did that before: I can do that again.' I feel that if you're a writer, you're always at work. Even when I'm done writing at noon, I've got my antennae up for a film that I see or a conversation or if I'm reading something else. I don't just write from eight to four and then knock off. My subconscious kicks in when I'm sitting down with my wife and I get the thousand-yard stare in my eyes and she's like, 'Okay, I know where he's at right now', and she doesn't bother me. Hands raised, palms up I feel like I am totally blessed that every morning I get to figure out a way to spend time with both my devotion, doing my scripture reading, and my avocation, which is to write. Poetry doesn't pay the postage, but you don't write poetry for the money. You write it because you can't not write it. I'm blessed because at the same time in the morning, I'm having a spiritual experience as well as an aesthetic experience...It's like standing in church with your hands raised, palms up: 'What is it you want to give to me today? I'll take it. I'm just going to be an open vessel for you here.' Carl Winderl holds a Ph.D. in Creative Writing from New York University and maintains a home in San Diego, California.

Carl's other work on Foreshadow: At Judas' funeral (Poetry, March 2021) Josh Seligman is the editor of Foreshadow.

1 Comment

'Music and Memory' by Alfred Noyes Music, that is God's memory, never forgets you. Music, in atom, and star, and the falling leaf, Binding all worlds in one, remembers for ever The least light whisper and cry of our joy and grief; Chord calling to chord, through swift resurrectional changes, From key to key, in the long unbreakable chain . . . All, all that we ever loved, though it sleep in the silence, At a touch of the Master shall wake and be music again. Alfred Noyes (1880–1958) was an English poet.

By Susan Yanos “Call me Ishmael.” So begins Herman Melville’s gargantuan epic of the great white whale, Moby Dick. Now don’t worry, I’m not recommending the novel for your summer reading list, but as I have been thinking about the personal story and the spiritual journey, Melville’s narrator has been haunting my dreams—until I realized that it was reading this novel that first got me interested in why we tell stories. I am a spiritual director, but I am also a writer and writing teacher. Over the years I have watched numerous students struggle to write the stories of their lives—in memoirs and non-fiction essays, or fictionalized in short stories and novels, in poetry, and in spiritual autobiographies. What I have seen over and over again is the power of story writing to reshape how people think about themselves and their world, about God and faith. Story theologians have said that stories serve three very important functions: world building, truth seeking, and self healing. In fact, some of my more astute students have noticed that writing is indeed spiritual work, and it was this that led me into spiritual direction. Now as a writing teacher, I have all kinds of suggestions which help writers go through this process, but it has taken some time and struggle to figure out how to be with spiritual directees when they bless me with the stories of their lives. It has taken even longer to figure out how to be with myself as I tell my own story, and often I am not a very good companion! Fortunately, Melville’s narrator whispers through my dreams. Call me Ishmael, he says, and we know immediately that this is not his given name but the name he chooses to give, perhaps just for this audience, just for this telling of the tale—and many readers of the novel get the impression that this is not the only time Ishmael has told his story, that indeed he has told it many times, may perhaps tell it many times more to any audience who will listen, whether willingly or not. He’s driven to repeat it, trying to understand why he alone survived while the rest of the crew died—many of whom he deems to be much better men than he. You’ll remember that in the Bible, the oceans are representative of the great forces of chaos which God did not destroy but bound within their basins. Deep within them dwells the monster of chaos, Leviathan, sometimes described as many-headed or as a crocodile or—pertinent to our Moby Dick tale—as a whale. Often storytelling is the ship we sail over the watery chaos of our lives. We tell our lives’ stories to protect us from the turbulence which threatens to pull us under, or when we do go under, to somehow find meaning in the struggle, in the confusion and fear, in the suffering and pain. Like Ishmael, we tell the same stories over and over again. Perhaps you have witnessed this in family members who have undergone some trial and cannot let it go, or in yourself. Henri Nouwen, in his book The Inner Voice of Love, writes, “There are two ways of telling your story. One is to tell it compulsively and urgently, to keep returning to it because you see your present suffering as the result of your past experiences.” Nouwen wrote this book during an intense emotional and spiritual crisis. By studying his own urges and compulsions, his own desire to tell his story, he came to see that there is another way, a way to tell your story “from the place where it no longer dominates you,” where the compulsion to tell it is gone. Such an approach requires distance, as well as the vision to see the telling as the way to freedom, and the wisdom to know that the past does not need to control the present. Nouwen wrote that then the past “has lost its weight and can be remembered as God’s way of making you more compassionate and understanding towards others.” So this telling and retelling are important, are necessary, because although we cannot change the relentless reality of the plot, we can change the role we choose to play. We can move from the victim of the story of our lives’ events to its survivor, to its hero. (I’m not suggesting that this is the ideal trajectory for our personal stories, but it gives an idea of the change that is possible.) Some argue that this change is so mind-altering that it is, in fact, a re-writing of our personal histories. I prefer the term re-visioning to re-writing. We see order where before there had been nothing but chaos, meaning where there had been only perplexity, a glimmer of beauty in the ugliness oppressing us, light in the shrouding and suffocating darkness. This all takes time—much time—and much patience as we go through the many retellings. And it takes a sensitive ear to pick out the subtle shifts in the story and bring them to our notice, along with a gentle reminder that God did not destroy the waters of chaos. Therefore, God is in the darkness as well as the light, in the ugliness and perplexity as well as in the beauty and meaning. God is in our hunger as well as in the loaves and fish that feed us. Ultimately, this is not an intellectual task, but a heart task. All this has led me to two questions I struggle with personally. First, how best to help directees—and myself—see God’s presence in all aspects of our lives, especially in the watery depths where Moby Dick smashed Ishmael? All too often we don’t feel that Presence. I trust that God will reveal in God’s own time, because I know that too often we are not ready to receive a direct assurance from others. We have first to experience fully what appears as God’s absence. But having said that, is there nothing I can do to help? Second, what about those times when we get stuck in the telling, when we get lost in our own stories by becoming so absorbed with ourselves that we fail to see the larger themes of the story unfold? I want to know how we move from a compulsive storytelling—because locked in the past—to becoming open, aware, receptive, and trusting of the spiritual process, even to the “stuckness” itself, as well as to the grace within the telling, to any movement away from letting the past dominate the story, to God’s presence amidst God’s seeming absence. For me, one key is to remember that just as Moses feared that he would be destroyed if he looked upon God’s face, begging God to show him just the behind, we too can often be destroyed by a too direct look at truth, especially the unpleasant truths about ourselves—or at least be so overwhelmed by them as to be unable to take them in. Such is the case for Melville’s narrator. Unable to take in the truth, he walks all around it by cataloguing every inch and pound of a whale in tedious chapters that most readers skip because, they complain, those chapters cause as much misery for them as the ship’s crew endured in its battle with the whale. The narrator thinks that he can eventually comprehend the mystery that is Moby Dick, as well as Captain Ahab’s need to conquer it, by studying mere facts. I think that’s what happens in a lot of storytelling I hear from folks—this almost compulsive need to record every detail. But that’s approaching it with the intellect. Remember that getting beyond story compulsions is heart work. To engage the heart, we can tap into the imagination. Stories are so powerful because they combine the language of reason (declarative sentences, facts and explanation) with the language of the imagination (dreams, fantasies, the subconscious). Psychology has revealed that the imagination carries truth, but perhaps more important, the imagination allows us to hold contradictory elements in tension. Consequently, the language of the imagination can lead us more deeply into ourselves, becoming ways to face indirectly truths we are unwilling or unable to face directly. Such language carries deep insights which we cannot verbalize. Many years ago, I discovered that students writing memoir instinctively chose images that resonated with them, but they didn’t know why and frequently didn’t even realize they’d done so. My job was to pay attention and then call their attention to the images. For instance, a young woman brought to workshop several short vignettes, including a story about her childhood cancer and another about how she thought a ghost lived in her childhood home. She believed nothing connected the pieces and wanted to throw most of them out and start over. I encouraged her not to, and eventually she began to see that her life was haunted by more than one specter. The largest specter was fear—the fear to dream of the future because her cancer might not remain in remission. Bringing that ghost into the light not only made for a good memoir, but it seemed to destroy the past’s power over her present. The ghost still inhabits the house—an appropriate metaphor for the self—but she found it is a pretty large house. Or there was the student who wrote about a tornado that swept through her town, which she later saw as part of a pattern of imagery centered around destruction, revealing the dysfunction in a family marred by abuse. Or the student who came to understand her bungee jumping as a metaphor for the uncertainty of her life because she was born with a hole in her heart. These stories stunned the students’ classmates with their profound beauty, a beauty which resulted because the storytellers were willing to sit with the chaotic jumble of fragments they had generated until they could see links between them. The stories became a way for them to tell their truths indirectly, to let the images and the structure reveal deep insights which they could not, and probably still cannot, verbalize directly. By the way, these students were not extraordinarily gifted writers, nor did they have years of training as writers. Therefore, one strategy we can adopt is to note the images which appear in our storytelling, explore them further, and be willing to sit with the resulting chaos. Researchers have noticed that the distinguishing characteristic between a good and a poor writer is the ability to tolerate chaos. Neither writer likes it, but while the good writer endures the tension, the poor writer will grasp at the first idea that comes along simply to be rid of the unease. The same, I think, is true of the spiritual journey. Any time we can engage the imagination, there’s the potential for mess and chaos, but also the potential to bump the story out of the rut it’s stuck in. Another strategy I’ve stumbled upon is to re-write the ending. If I don’t like how I responded to someone, I re-write it. I challenge myself not to stop with merely changing what I said, but to go further and see the experience as a scene with consequences: what will happen next and next and then after that? What if you hadn’t received that wound, been scarred in just that way? Re-write the story so that everything leading up to the injury stays the same, but the injury doesn’t happen. Don’t stop there, because I suspect you’ve already done this step. Go on with the story. Imagine the consequences. When Melville’s narrator demands that we call him Ishmael, we suddenly realize that he is telling his truth, although indirectly, by linking with another Ishmael, the first-born son of Abraham, first born but not the true heir, not the favored son, not the better son. A slave yet more than a slave, he and his mother, Hagar, are driven into the desert alone, exiled, abandoned, condemned to wander far from home—a fate the novel’s narrator feels he shares. So a third strategy I’ve learned is to connect my personal story with one of the great stories of literature, because when I am able to do so, interesting connections are forged through the imagination. Biblical stories and ancient myths are particularly powerful vehicles for this, one reason being they rarely provide the psychological insights or emotional filler that we’ve come to expect from more contemporary storytellers, thus leaving important gaps which we must fill. I’ve been reading the story of the Gerasene demoniac in Mark’s gospel lately, and noticed that even though he begged Jesus to allow him to come along on the journey with the disciples, Jesus told him to go back home, back to the very people who chained him in that graveyard as if he were already dead. What was that like, I wonder. Did his family and neighbors marvel at the miracle and praise God, or did they watch him warily, unwilling to get close emotionally, never trusting him because it would surely be just a matter of time before he snapped and once again hurt them. People don’t really change, you know, I can hear them say behind closed doors. Such gaps in the plot and in the characters’ emotions force us to imagine what is missing, and it is this opening that allows us to examine our own situations within theirs. Think of the implications of this for the self-awareness that is necessary to understand our lives. After Nouwen wrote The Inner Voice of Love while undergoing six months of spiritual and emotional care, he wrote what I consider his most beautiful book, Return of the Prodigal Son, where he explores his own past by immersing in the parable, in Rembrandt’s painting of the parable, and in Rembrandt’s life. Counting his own biography, he imaginatively mined, compared, and wove together four stories. Let me give you a personal example. Unfortunately, I had a falling out with some family members. It was a difficult time, very difficult. Now this is going to sound really geeky, but then I am a literature geek: one morning I woke up with Odysseus’ black ship in my head. I began to see my situation as a scene from the Odyssey. The scene I had in mind was when Odysseus had to sail between a rock and a hard place. Rather than take a much longer but safer route, he chose rather arrogantly to navigate between the deadly whirlpool named Charybdis and the rocky lair of the many-headed monster, Scylla. As you’ll recall, he doesn’t make it. Scylla’s heads lunge down and eat some of his crew, his ship gets sucked into Charybdis’ mighty maw and is destroyed, the crew drowned. So I imagined Scylla’s heads bearing the faces of my family members and began to draw in my sketch book a very bleak scene. My ship was going down, caught in the whirlpool of my anger. I wasn’t going to make it either. Then I remembered the rest of the story. Odysseus nearly drowns, but he does not die. Instead, his clothes are ripped from his body by the currents and he’s swept upon the shores of a beautiful island, naked as a newborn or as a newly baptized neophyte, younger looking and more handsome than before. I know, I want to get ahold of some of those sea salts for my beauty regimen, too. On the island, he is offered a new life with a new and younger wife, a new kingdom to rule, and years of peace without conflict and the suffering conflict engenders. But that is not who he is. He says thanks but no thanks, and returns to his true wife, Penelope, and much conflict and suffering as he reclaims his own kingdom from those who tried to replace him while he was gone. In the far corner of my drawing, I drew myself washed up on a beach. Identifying my story with Odysseus’ story helped me get unstuck from the details of my experience and express what I had not been able to before. Yet knowing the whole story challenged me to see that I had choices before me. I was not a victim assaulted by invincible monsters or trapped in the watery depths. And because I understood why Odysseus chose to go home, even though he risked life to do it, I became more aware of the options before me and what I needed, what I wanted to do in this situation. Call me Ishmael. Call me Odysseus. Call me Ophelia or Jack the Giant Killer, Ruth or Naomi. Some have defined humans as creatures who think in stories. Others have said the basis of ministry is not to serve others but to enter into their stories. We could explain the Incarnation as God entering the story of humanity. Once we enter a story, nothing is ever the same. Susan Yanos is the author of The Tongue Has No Bone, a book of poems, and Woman, You Are Free: A Spirituality for Women in Luke; and is co-editor and co-author of Emerging from the Vineyard: Essays by Lay Ecclesial Ministers. Her poems, essays and articles have appeared in several journals. A former professor of writing, literature and ministry of writing, she now serves as a spiritual director, retreat leader and freelance editor. She lives with her husband on their farm in east-central Indiana (US), where she creates art quilts and tends to her hens, fruit trees and gardens.

Susan's other work on Foreshadow: God Who Sent the Dove Sends the Hawk (Poetry, January 2021) Love Song of the Anawim (Poetry, April 2021) 'Distant Voices' by Alfred Noyes Remember the house of thy father, When the palaces open before thee, And the music would make thee forget. When the cities are glittering around thee, Remember the lamp in the evening, The loneliness and the peace. When the deep things that cannot be spoken Are drowned in a riot of laughter, And the proud wine foams in thy cup; In the day when thy wealth is upon thee, Remember the path through the pine-wood, Remember the days of thy peace. Remember--remember--remember-- When the cares of this world and its treasure Have dulled the swift eyes of thy youth; When beauty and longing forsake thee, And there is no hope in the darkness, And the soul is drowned in the flesh; Turn, then, to the house of thy boyhood, To the sea and the hills that would heal thee, To the voices of those thou hast lost, To the still small voices that loved thee, Whispering, out of the silence, Remember--remember--remember-- Remember the house of thy father, Remember the paths of thy peace. Alfred Noyes (1880–1958) was an English poet.

Doreen Nyamwija shares lessons learned through working at the Iona Centres, Scotland One of the practical things that attracted me to work here, after my time as a volunteer, was seeing people with normally big or important roles working alongside people with less important roles. For example, after seeing Sharon, the Deputy Director, and the rest of the team (whom she oversaw) washing the dishes together, I was humbled. To me, this was a symbol of discipleship, being servants to one another. We need more leaders than bosses in this world. Things may not always be as good as they should be on Iona, but this kind of “discipleship leadership” is still demonstrated in lots of different ways here. I pray and hope it spreads. During the season, I tell volunteers that I am their line manager but I am always open to new ideas. Knocking down the building and rebuilding it in a day might be wishful thinking, but ideas that are within our means and practical, we can consider. People often come up with good ideas to improve something that irritates them. For example, one of the volunteers hated the fact that the kitchen in the MacLeod Centre got very congested when everyone was trying to set up the tables for meals; he hated people coming one by one to wash their hands in the kitchen. So, I asked him what his solution would be. He suggested installing a sink in the common room, which would reduce the congestion in the kitchen. Later I told my line manager, who took it further, and now this has been done and does make a big difference. People often think that the sink has always been there or wonder how this could not have been pointed out before. Doreen Nyamwija holds a business degree in entrepreneurship and for four years worked as the head housekeeper for the MacLeod Centre on the Isle of Iona, Scotland. She has established a charity providing accessible toilets for schools across Uganda, and she is currently working to build an accessible bed and breakfast for locals and visitors in Uganda, where she lives with her husband and their two children. To find out more about her B&B project and how to support it, visit the website here or email her at [email protected].

This piece is an excerpt from Doreen's book Never Give Up: My Life Story from Uganda to Iona (Cloister House Press, 2017). After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google, Podomatic, Player FM and Deezer. Listen to other Forecasts here. Ken Deeks, an active therapist and the leader of a folk group, describes the importance of treating people not foremost as clients or numbers but as humans, people whose names and lives are remembered and cherished. For him, being a Christian involves having this attitude and taking Christ with him wherever he goes. Ken also performs the Scottish folk song 'Black is the Colour of My True Love's Hair'. Host: Josh Seligman. If you are interested in purchasing a copy of The Beech Band Tune Book, email [email protected] and Josh will put you in touch with Ken. Ken Deeks is an active therapist and folk musician based in Manchester, UK.

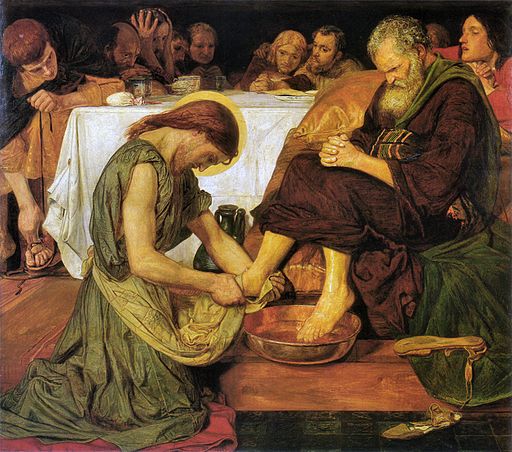

Josh Seligman is the editor of Foreshadow. 'The Windhover' by Gerard Manley Hopkins To Christ our Lord I caught this morning morning's minion, king- dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing, As a skate's heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing! Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier! No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear, Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion. Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) was a British painter.

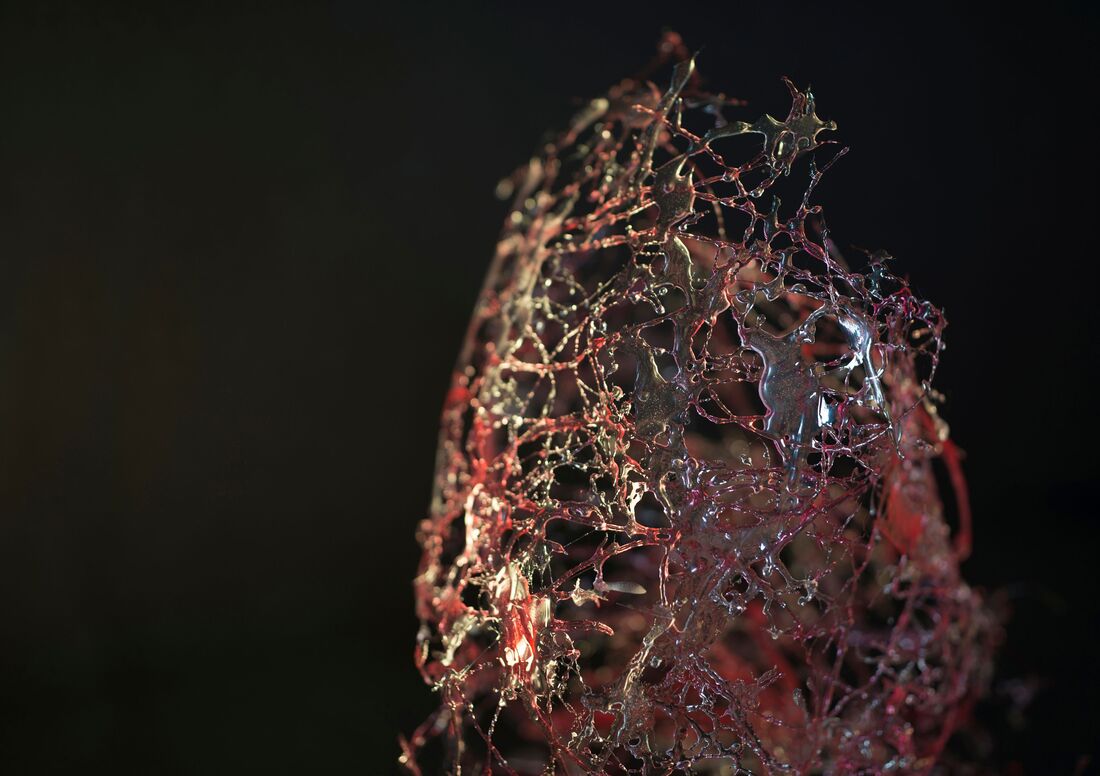

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) was an English poet and a Jesuit priest. By Urzula Glienecke Blood vessels – arteries, veins and capillaries – surround our inner organs like a complicated river system, a fragile mesh in which life flows. It reminds me of the fragility of life but also of how God is closer to us than breathing, closer to us than we ourselves. - UG Urzula Glienecke, PhD, is a Latvian theologian, artist and activist living in Scotland. Urzula is a Member of the Iona Community. She is passionate about social justice, the environment and empowering people at the grassroots level.

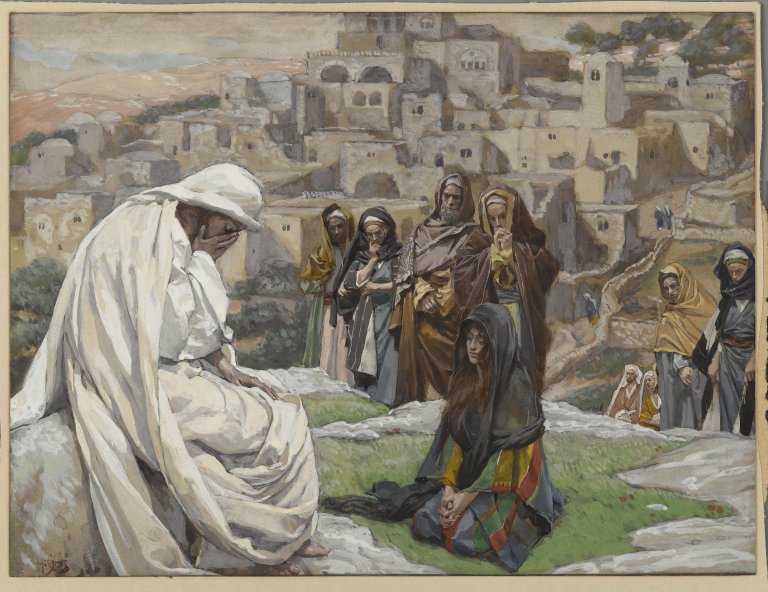

Urzula's other work on Foreshadow: A Foretaste of the Kingdom (Non-fiction, April 2021) By Tim Harvey One of the occupational hazards of pastoral ministry is that people occasionally try to trap you on controversial issues. To be fair, sometimes people trust you and simply want to learn more. But not always. So when Bill (not his real name) said, “Are you really OK injecting aborted baby parts into your arm?” I knew that even though we would continue talking, our conversation had effectively ended. My biggest challenge in that moment was managing my own response. While I disagree with Bill’s opinion on Covid-19 vaccines, what frustrated me the most was his opinion of me. As I measured my own declining credibility in his facial expression and tone of voice, I could feel my own fight or flight response rising. How would I respond? It is tempting to view someone like Bill as a right-wing conspiracy theorist to be mocked or cancelled for the views he’s come to hold. But such a response misses the point. Bill is not a bad guy; he’s quite talented, runs a successful small business, and enjoys staying up to date on the issues of the day. He can speak in depth on any number of topics, political and otherwise. What makes conversations like these difficult is that Bill gets his news from one place on the political spectrum. He has constructed an echo chamber that not only confirms what he already suspects, it also tells him how he should interpret differing viewpoints. Because the trusted voices in his echo chamber tell him that the mainstream media is both fundamentally dishonest and dangerous to our country, any attempt of mine to offer a differing view of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines—no matter how carefully researched—becomes not a counterpoint to be discussed but a heresy to be defeated. People who think differently than he become enemies. The thing is, on a certain level I understand where Bill is coming from. Christian theology teaches us that we are “aliens and strangers” in this world. One doesn’t need to live on the theological or political right to understand that praying “your kingdom come…on earth as it is in heaven” means that the kingdoms we see aren’t the ones we’re hoping for. Humans, regardless of our spiritual or political beliefs, are ultra-social animals whose need to be a valued member of our tribe is more important than being right. Each of us—not just the Bills of the world—belong to a tribe that offers value and meaning to our lives. But membership in a tribe comes with great pressure to conform to the values of the tribe. This pressure to conform makes it difficult to hear, let alone engage with, contrary viewpoints. Whether we ascribe this to millions of years of evolutionary development or to our fallen sin nature, leaving one tribe for another requires nothing less miraculous than Christian conversion. So how can I respond? I can mourn. I can mourn what might be the loss of a friendship I’ve come to value, one where I had assumed those feelings were mutual. I can mourn the fact that someone I admire on so many levels no longer seems to admire me nor respect my opinion. I can mourn the fact that being members of the same congregation does not mean we belong to the same tribe. In the Beatitudes, Jesus tells us, “Blessed are those who mourn.” As a pastor, I’ve learned a thing or two about mourning. I’ve heard doctors say to families, “we did all we could.” I’ve sat with a family when the funeral director closed the casket for the last time. Mourning comes with the territory. But I never considered I’d one day mourn the loss of respect and trust from a friend whose political perspective convinced him that I am not to be taken seriously. My mourning makes it difficult to hear the second half of Jesus’ beatitude: “for they will be comforted.” Honestly, I think it would be easier to lash out at Bill—or at least forward him a few articles. It would lessen the weight of the cross I’m bearing these days. For now, my main task is to accept that Bill and I live in different echo chambers. A different set of voices shapes my world. I need to find the comfort that comes to those who mourn before I do anything else. Tim Harvey has served as pastor of Oak Grove Church of the Brethren in Roanoke, Virginia, since 2015. He and his wife Lynette have been married for 28 years and have three young adult children and one son-in-law. Tim has written extensively for various Church of the Brethren publications, including magazine articles, worship resources, Bible Study and other devotional materials. When he is not in his office, Tim enjoys woodworking and half-marathon running. 'Death, be not proud' by John Donne Death, be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery. Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell, And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then? One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die. James Tissot (1836–1902) was a French artist.

John Donne (1572–1631) was an English poet and an Anglican priest. |

Categories

All

ForecastSupport UsArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed