|

'The Kingdom' by R. S. Thomas It’s a long way off but inside it There are quite different things going on: Festivals at which the poor man Is king and the consumptive is Healed; mirrors in which the blind look At themselves and love looks at them Back; and industry is for mending The bent bones and the minds fractured By life. It’s a long way off, but to get There takes no time and admission Is free, if you purge yourself Of desire, and present yourself with Your need only and the simple offering Of your faith, green as a leaf. R. S. Thomas (1913–2000) was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest.

0 Comments

By Emma McCoy I have become a covenant, beautiful and new. I will walk faithfully, like the blameless and God said “I will make nations out of you.” I looked at the stars, the ones I thought I knew and whispered “I will no longer be aimless” for I have become a covenant, beautiful and new. I swallowed my fear in the lands I passed through and whispered “I will not be left nameless” and God said “I will make nations out of you.” God gave me a son; it was something like a preview of His love. Our laughter was shameless because we have become a covenant, beautiful and new. I held nothing back. In my obedience I brought my joy to the LORD even when it would leave me claimless and He said “I will make nations out of you.” In my old age there are things I know are true: My God is faithful and changeless; I have become a covenant, beautiful and new and God said “I will make nations out of you.” Emma McCoy is a literature student at Point Loma Nazarene University, California. Much of her poetry explores biblical narratives through re-imagination, closed forms and a close look at the structures and imagery of the original stories. When she's not writing, she spends her time outdoors chasing the downhill -- either skiing or mountain-biking.

By Scott Stevens After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the music to load. As I try to write about "Perspective" this afternoon having just watched footage of mobs assaulting the Capitol in Washington, I am aware of the melancholy and quiet strength in this piece. Listening to it provides a stark juxtaposition to the displays of violence and unrest being broadcast. To me, the music encourages reflection, tells of the sadness of the times, yet conveys courage -- even if it is a fragile one. Covid-19 still weighs heavily upon us all and yet we each dare to hope, to strive, and to live into the unknowns of our futures. We carry hope in one hand and lament in the other. Courage and sadness are not mutually exclusive. While I enjoy hero stories and bombastic soundtracks, "Perspective" is not a conventionally heroic piece. It is neither flashy nor daring. Instead, "Perspective" engenders simplicity: a theme that runs throughout my 2020 release. The true heart of this piece emerges after one minute, when all is cleared away save for a simple piano motif. Without the armor of the orchestra, a simple tune remains to decide for itself whether to give up or continue on. - SS Scott Stevens is a composer whose versatility stems from eclectic influences. His music (listen on Spotify) is featured in multiple independent film scores as well as ads for Toyota, Saatchi & Saatchi and Red Bull, among others. Scott holds a Bachelor’s degree in Music Composition from Point Loma Nazarene University and a Master’s degree in Global Music Composition from San Diego State University.

Scott's piece 'Dawn Will Prevail' was published in Foreshadow in December 2020. I took this photo in 2016 on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi during a field trip with my photography students. This is the Halemaʻumaʻu Crater on Kīlauea as part of an ongoing eruption that continues to this day. - AS

By Susan Yanos From the kitchen window I watch as doves waddle clown-like round puddles of corn spilled near the grain pit, then fly into vents gaping on bins, or from guy wire to wire like trapeze artists with toes reaching sure for lines stretched taut from grain leg to the ground. No net below. As I go about my chores, I hear them inside the bins, invisible feathers whispering against metal walls. When I straighten from pulling weeds in the garden, mind elsewhere, their cooing warbles me back: dirt smudged on knees, green juice staining fingertips, sweat at hairline. Sometimes they wheel above barns and house, gray discs in the sun. Flying rats, our hand mutters, and begs to shoot at them, tired of smeared windshields and levers. This year an albino has bred white under dusty plumage of its kin. Over our farm’s endless browns and dull greens, their beauty wings. They were the first to die after the hawk moved in. Our black-and-tan found a carcass in the yard and brought it to the back door, bloodied white feathers fringing her mouth. Yesterday I found another near the chicken coop, eyeless. I check the latch before I leave, scanning the sky. Now no birds clown round the grain pit nor coo from the wires. Feeders near windows sit full; suet cakes hang whole in the lilacs since all finches and cardinals abandoned us. I must do my chores with no feather to change my sight, wondering why it is I fed doves, drawing hawk. Today a shape appeared in the lilac’s belly: a bag blown in by night, I thought, or rotted garbage. But it turned, revealing beak hooked and smooth, and looked at me. Though I looked hard, I could not see beyond those eyes. Not moving, its talons gut my tamed truths, expose my soul. Susan Yanos is the author of The Tongue Has No Bone, a book of poems, and Woman, You Are Free: A Spirituality for Women in Luke; and is co-editor and co-author of Emerging from the Vineyard: Essays by Lay Ecclesial Ministers. Her poems, essays and articles have appeared in several journals. A former professor of writing, literature and ministry of writing, she now serves as a spiritual director, retreat leader and freelance editor. She lives with her husband on their farm in east-central Indiana (US), where she creates art quilts and tends to her hens, fruit trees and gardens.

'God Who Sent the Dove Sends the Hawk' was first published in Saint Katherine Review before appearing in The Tongue Has No Bone. Dean Nelson on removing distractions to encounter divine love Almost every morning since I’ve been working from home these past few months, I watch my neighbors argue. I open my garage door, set up my stationary bike in the driveway, pedal hard for about 30 minutes and observe the drama. It’s amazing how that tiny bird can dive-bomb the much bigger and noisier crow. They squawk and chirp at each other as they shoot straight up in the air, straight down, the crow making evasive maneuvers that the pilots at the nearby Miramar air station can only dream about. When the big crow finally flies to a nearby pine tree, the little bird flies back to the top of a palm tree, just a few feet away. The two still face each other and argue from their respective perches. Classic schoolyard taunting, only in different octaves. Something about each other’s mothers, no doubt, with maybe an occasional “… and the horse you rode in on!” Then the crow glides toward the palm tree and the aerial battle picks up again. Eventually the crow gives up and flies away, squawking something like “You haven’t seen the last of me!” The little bird returns to the top of his tree, where presumably there is a nest to protect, and remains silent and attentive. I’m thinking that this is what the quarantine has been like. Some of my writer friends feel that it’s really no different from the way they typically live, hunkered down in front of their computers or notepads, reading, researching, typing. They’re used to isolation. But most of us aren’t. And if there is a silver lining in this pandemic cloud, it is that many of us have been forced to confront what it means to be by ourselves without the usual distractions. In 1654, the scientist and philosopher Blaise Pascal wrote, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” There is even some research at the University of Virginia to back that up.[1] I would augment that to include our inability to take a walk in our neighborhood without looking down at our phones. Why is it so hard to live without distractions? What are we left with when we don’t have them? We just have ourselves. Which may be a good thing. Or not. Even in quarantine there are still some distractions worth chasing away. Like that crow across the street, they are taunting us, and even trying to invade our personal space, demanding our attention. Not all of them deserve our constant consideration, though. As a journalist and a journalism professor, it pains me to tell my friends to stop having a constant flow of news into their homes. Keep informed, I tell them, but do it in small bites. Much of what is posing for news is repetitive at best, and speculative and incorrect at worst. Dial it back and turn it off for a while, I tell them. And social media feeds aren’t really feeding you. They could be poisoning you. Just sit with yourself a bit, I tell them. There are some good discoveries to be made there. As the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer said, “It is difficult to find happiness within oneself, but it is impossible to find it anywhere else.” But that crow of distraction is relentless. Several years ago two friends and I trekked and camped in Tibet. The first few days I suffered from altitude sickness — we were at 17,000 feet — that rendered me useless for any adventures. But if you’re going to be forced into contemplation, Tibet is the place to be. I could sit in my hostel room and listen to the bells and the chants from the nearby temple, and inhale the incense from down the hall. My head pounded as if a railroad spike had been driven into it, but I sat and listened and breathed. It was excruciating. Sometimes I sat in a temple, lit only with the heavily scented yak-waxed candles. One evening I sat at the edge of a lake where Tibetan Buddhist monks are said to have seen visions. I began to get used to sitting quietly because it was all I could physically do, and eventually the throbbing in my skull began to wane. My friends and I went to a village velcroed onto a mountain slope, and decided to split up for the day. We didn’t set a time to reconnect. We just said we’d get back together somehow, somewhere, eventually. I hiked along the edge of a river that was moving with such ferocity that it easily turned a prayer wheel the size of a grain silo built into its banks. I gazed at the prayer wheel and river for a very long time, feeling the knot in my brain slowly loosen. I had a book and a journal in my backpack, but for some reason I didn’t take them out. A gray, long-haired horse wandered over and stood next to me. We looked at one another for what felt like several minutes. Neither one of us had anywhere we had to be, so we just remained there. I gave him part of my granola bar. Eventually, I closed my eyes and just listened to the river and the breathing of the horse. I could feel my mind race at first (how long was I going to sit here? How will I find my friends again? What is the next school year going to be like? Am I hungry? How does my head feel? Are my legs falling asleep?), but then it gradually slowed down to … nothing. I began thinking of the people I loved. My wife, my son, my daughter, and tears began flowing from my eyes. Not sobs. They were like the river — plentiful and steady, coming from a deep, deep place in a mountain that had developed an opening. And one word kept coming to me. Gratitude, gratitude, gratitude. The Persian poet Rumi wrote, “Observe the wonders as they occur around you. Don’t claim them. Feel the artistry moving through, and be silent.” That day in Tibet I observed and felt the silence, and was overwhelmed by the love that filled in. I wonder if this is what Jesus was getting at when he said, “The Kingdom of God is within you.” The Christian missionary E. Stanley Jones wrote this in the 1940s, but he could have been writing about it now, as our cities are boiling over and our authorities ignore the real issues that have caused the eruptions: “The outer arrangements of men are awry because the inner arrangements of men are awry. For the whole of the outer arrangements of life rests upon the inner. Men cannot get along with each other because they can’t get along with themselves.” Seems like we’re battling a virus from the outside and a virus from the inside. This morning I went out to my driveway and started riding my exercise bike, ready to watch the avian battle across the street. But today, there was no crow. The small bird sat at the top of the palm tree. Nothing was happening. Except the bird was singing. -- [1] 'A new study found people are terrible sitting alone with their thoughts' Dean Nelson is the founder and director of the journalism programme at Point Loma Nazarene University. His most recent book is Talk to Me: How to Ask Better Questions, Get Better Answers and Interview Anyone like a Pro (2019).

'Finding Healing in Lockdown' was first published in The San Diego Union-Tribune. Standing in the redwood grove, I am awed by the heavenly streaks pouring through the forest, and the silence is deafening. - SS

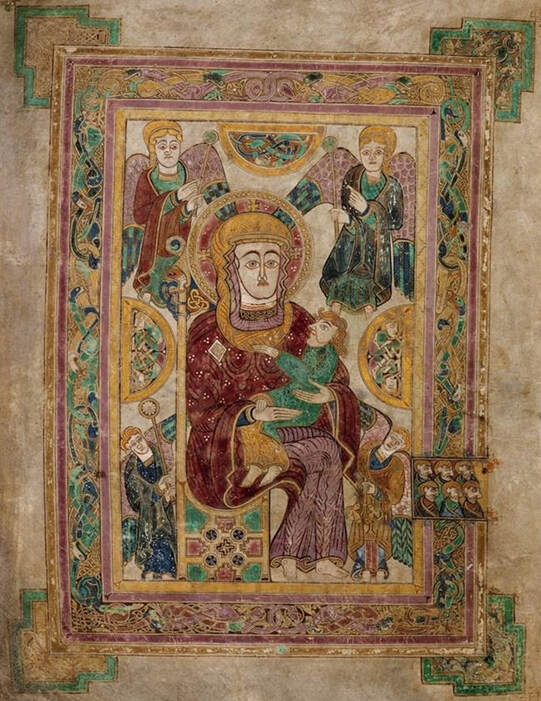

Rosemary Power describes an image of the Virgin Mary presenting the Christ. Near the start of the Book of Kells, a (Latin) Gospel Book made in about the year 800, most probably on Iona, the island west of the Scottish mainland, comes a portrait of the Virgin and Child (folio 7v). The image is small; within it, Mary is massive, dominating the space within the elaborate frame, crammed as it is with detail. Her pose and her presentation echo the icons of the Eastern Church, and she has a stylised nose and small mouth, with large, almond-shaped eyes and a distant, contemplative gaze. She is seated on a high-backed chair, whose base is decorated with a jewelled cross, and whose back ends in a lion’s head — perhaps indicating that Jesus, Lion of Judah, is supporting her as she holds him in his infancy. She is dressed as a woman of wealth, with the headdress of a Roman matron. The jewelled brooch at her breast adorns garments that were perhaps once purple, and that have the light, clinging sense of silk. Her halo has a decorated rim, and connects to her head through three shining crosses. Jesus is even more stylised: the Lord of creation, as well as the child in her arms. His body is of adult shape, and he has long, wavy hair and a beard-line: it is one of the features of the Book of Kells that he later grows a full beard. The faces, hands, and bare feet of both figures are all whitened — the Northern European way of displaying light as coming from within, comparable to the Eastern way of painting over gold leaf. The figures also have their human aspects. The Eastern models have been adapted to display humanity in Northern Europe: light-coloured hair and blue eyes — something that we have taken as normal, and forgotten that it was once novel. A single curl escapes from Mary’s head-dress. Jesus, his eyes on his mother, dangles his feet and stretches one hand across her breast, while the other clutches her right hand. Both Mary and the angels have legs, and she has breasts with nipples visible through her clothing: she is a nursing mother. Mary holds Jesus protectively, although with her hands — with the palms strangely turned outwards — she offers him to us, the onlookers. The four surrounding angels are full of movement. Two above the head of Mary indicate the scene, and their translucent clothes give a sense of movement, while their wings show through Mary’s transparent halo. The two below peep playfully around her chair. There are half-circle panels on each side, within which two figures have legs entwined as if dancing, perhaps representative of the humanity for whom the incarnation comes about. In another half-circle above are bird-headed creatures with elongated bodies; similar figures interweave within the border. They may be representatives of the heavens, showing — as we find elsewhere in this work with its complex, interconnected imagery — that all creation sings praise of the incarnation. Rosemary Power is a medievalist and writer whose new book Praying with the Book of Kells will be published by Veritas, Dublin, in 2021. This article has been extracted from one published in Church Times (18/25 December 2020) with the author's permission.

|

Categories

All

ForecastSupport UsArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed