|

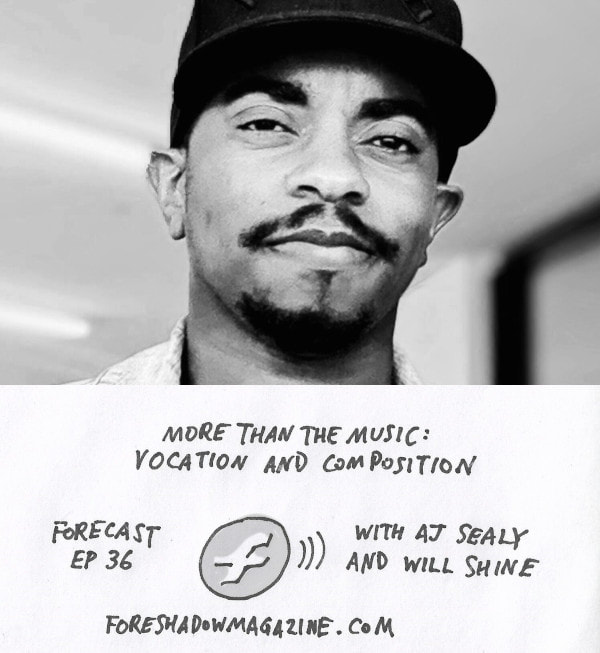

After clicking 'Play', please wait a few moments for the podcast to load. You can also listen on Spotify, Apple, Google and other platforms. Listen to other Forecasts here. AJ Sealy speaks with Will about how he became a composer and the joys and challenges that have come with his career, from maintaining a work–life balance with his family to industry barriers as a person of colour to pursuing humility in an environment of acclaim and status-seeking. For AJ, vocation is about both composing music and how he composes himself as a person, cultivating goodness in his relationships with co-workers, loved ones and other people in his life. AJ Sealy is a composer, producer and multi-instrumentalist based in Los Angeles, California. Find out more about his work here.

Will is a co-host of Forecast. Support us by sharing this post or buying us a book.

0 Comments

By Ryan Keating While the prophet exile sleeps Deeply Lying down Below deck In the dark With the rhythm of the waves He moves. After pagan panic awakens Insecurity Unreconciled Sacrificing himself For strangers In the storm He moves. In a burial at sea Resigned to Seaweed and salt Behind pain And potential While nations drown God moves. Ryan Keating is a writer, pastor, and winemaker on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. His work can be found in publications such as Saint Katherine Review, Ekstasis Magazine, Amethyst Review, Macrina Magazine, Fathom, Dreich, Vocivia and Miras Dergi, where he is a regular contributor in English and Turkish.

Related work on Foreshadow: The Sign of Jonah: Foreword (2022) (Editorial by Josh Seligman, January 2022) Jonah and the King (Poetry by Matthew J. Andrews, March 2022) Support us by sharing this post or buying us a book. Alice Wisler on helping bereaved parents through writing Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows. ~James 1:17, NIV You can do it, an elderly poet and bereaved mother had written when asking me to lead a writing workshop. Sascha was well-loved in Denver and supposed to be in charge of the event, but since she wasn’t feeling well, she asked me to fill in for her. Get parents to write, she told me. It all sounded easy, but it wasn’t so easy for parents who had experienced the death of a child. Bereaved parents are heartbroken. They’ve gone through the worst pain. They mourn; they shout. On their really bad days, they’ve been tempted to smack a dozen moms who have healthy kids and life-is-grand attitudes. They are critical when it comes to those who want to tell them how to grieve, especially those who have never had to bury a child. “The hardest room in the world,” described one psychologist who was asked to talk to a group of bereaved moms and dads in a church basement. After his acknowledgement, the room let out a collective sigh. All the judgmental stares slithered under the front door. Bereaved parents are a tough crowd, and I would be facilitating a workshop for them at a conference where I knew no one. It would have been reassuring to have at least one person sit in the front row to smile and nod. I did have one advantage: I was not an outsider. I was one of them, a mom who had lost my son Daniel to a cancer-related death. I was also familiar with the workshop’s topic of writing. Every time I wrote in my journals and tear-stained, dog-eared notebooks, I was spared from driving off a cliff or smacking someone who told me I’d see my son again in heaven, so there was no reason to cry. Even though I had never stood before conference attendees and shared how to write and why writing is beneficial to healing, I knew that writing had saved my life. When I asked Sascha for advice on how to lead the workshop, she wrote: Get parents to put two words together. That’s how it starts. Two words together. Two words lead to three, and so on. Weeks later, I flew from my home in North Carolina to Denver, Colorado. I took my place behind the podium as parents trickled into the conference room and found seats. I smiled and hoped that no one knew that I was a novice and this was my first lesson. Would I be able to convince the gathering that unleashing pain onto paper is a gift? I thought of the ways my pen and keyboard had pounded out poems, articles, and journal entries, and how those actions had brought me therapeutic clarity. Breaking into my thoughts was a question from a woman in the front row. “Do we have to write?” Her black T-shirt had Loved and Remembered printed in gold letters across her chest. The sign by the door to the workshop clearly said Writing Workshop, but this was no time to argue. “You can do whatever you feel comfortable with,” I said. “I don’t write well. I just can’t write about my son. I’ve tried. Each time I sit down to write, I just cry.” I was sure that was true because she was crying. “That’s okay.” When the room quieted, I introduced myself. I told a bit of my story: how my beloved Daniel was diagnosed with neuroblastoma at age three and died from cancer treatments eight months later at four years old. I spoke of his love of watermelon, the beach, and the original Toy Story movie. One of the exercises I’d prepared for the group was to write poems in honor of their children. While writing through pain is vital, being able to recollect happy memories of our children is a comfort on the journey. I read a few poems from one of Sascha’s books and then told the gathering to put words together even if it was just two at a time. Chatter stopped as each person bent over his notepad. I heard muffled tears, saw a few people wipe their eyes, and as I watched, I prayed for a positive outcome. I wanted word to get back to Sascha that I’d been a successful substitute. After ten minutes, I asked if anyone wanted to share his or her poem. No one said a word. Some looked uncomfortable. Then a hand shot up. “I’d like to read my poem.” It was the woman who said she didn’t write, couldn’t write. In a clear, animated voice, she read her poem. The lines spoke of how her son used to tease her that she didn’t like to cook, that the only thing she could make was microwavable meals. I heard laughter. The woman laughed, too. When she finished, the whole room clapped. Her smile was wider than the Colorado sky. Two mothers in the middle row nodded at me while others hugged those seated next to them. They got it! They understood the power of written words, of shared memories. I hoped they’d incorporate writing about their children into their weekly lives and that the process would empower them. Over the next years, doors opened, and I was invited to facilitate grief-writing workshops across the country. Writing for healing, health, and hope is a message I never tire of sharing. When I hear parents read their written words or tell me how writing has been a healing balm on their journey, I’m grateful to God for this good gift that starts with one solitary word flowing into another. Alice J. Wisler is the author of six novels, one devotional (Getting Out of Bed in the Morning: Reflections of Comfort in Heartache), and three memorial cookbooks. She teaches writing workshops across the country. Visit her at www.alicewisler.com.

Support us by sharing this post or buying us a book. |

Categories

All

ForecastSupport UsArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed