|

Book review by Rachel Fulton Brown I did not expect to enjoy this book. I tend not to like free verse—I much prefer iambic pentameter—nor do I enjoy most modern efforts to imagine what Jesus or Mary thought or said. The idiom is always off, not scriptural enough, too psychoanalytical or colloquial, making Jesus anything but divine and his mother either victim or “strong woman,” at once too ordinary to be hailed as “full of grace” and too powerful ever to have said “Let it be to me.” A book of poems written in Mary’s voice without meter or rhyme? At best, I expected to be irritated, if not downright annoyed. And yet, when Carl invited me to review his poems, I said yes, even as I questioned how it could be that I should find joy in them. What can I say? Mary has a way of nudging me when she wants me to look at something. The Song of Songs as sung at the feasts of her Assumption and Nativity, the psalms as sung in the Hours of the Virgin—these were the texts that medieval Christians turned to when they wanted to hear the voice of Mary speaking with her Son, about which I have previously written on other occasions at Mary’s behest. I say Mary’s behest, but more accurately, Wisdom’s, the voice of Our Lady conceived at the beginning of the world. I felt her nudge in Carl’s request. There is something here you need to learn. Do what he has asked you. Take, read. What would it be like to be the Mother of the Word when the Word became flesh and dwelt among us? To be filled with words, and yet silent, keeping them in your heart? One might catch a whisper here, a gesture there. The Spirit blows where it wills, overshadowing the letter. Sentences are reduced to fragments and promises, changes in font taken up from the Font. Each word becomes a riddle stretched out on the Cross of the page, crucified with the Son. There are glimpses of veils, shadows of types, the poverty of print made medium for the Light. “Do whatever he tells you.” Trust Him. Take it slowly. Have patience as you follow the lines down the page, collecting gemstones and drops of blood. It is cruel to ask a scholar to review a mosaic of Light, to render, dismember, shatter in prose. And yet who but a scholar—or lover—would catch every word? Hear the echoes of the tradition in the turn of half a phrase? The margins of the book fill with scribbled notes: I hate this effort to make heaven earthbound (on Mary sitting in the laundry, immaculately conceived). Like marginal labels in a medieval illuminated manuscript, glosses on images the poems assume (on Pilate’s wash water and the witnesses to His scourging). Mary knows the science of creation, quadrivium as well as trivium (on the chemical reaction of Good Friday’s leaded sky). Images leap out at you—tied to the creator of the world (“a lump of coal”). Sometimes it is difficult to tell who is speaking to Whom, when punctuation fails and no words are capitalized. Only the pronouns merit a capital letter, condemned: Him, His, He. Does the Son speak of the father or the Father of his son when Isaac lies stretched on the cross “trussed up, in trust”? Citations to Scripture are throughout unmarked, leaving marks in the margins, the imagery slipping from Old Testament to New and back again, shimmering, bloody, hidden in a life-time of prayer. Should I give my references? Tell you how I know that when Mary says (10) thus I now see and I know it’s not just a hypothesis, nor a theory it is Law that she is speaking the Reality of love, the transfigured Trinity made three-dimensional on the Cross buried in her womb, as medieval commentators like Richard of St. Laurent averred? Can I explain how I know, with Mary, that Christ was marked with tattoos—in Black and Blue Old English on his right bicep “Born to Raze Hell!”, a Serpent Green & Red on his left forearm, a Valentine’s Heart over His breast, broken in two, labelled M-O-T H-E-R (13)—because I wear tattoos of my own on my shoulders and back? Can I tell you how it makes sense to see the Transfigured Christ in the flying crosses of the airplanes, including the one flat, dull, shadow-less and life-less, on the ground in its hangar, awaiting its Passenger (20–21), because I have lived through the mechanical horror of air travel myself? Halfway through the book, the pain of understanding is almost (but not quite, because I am not Mary) too much to bear. Another marginal notation: Like eating the whole bar of chocolate in a single sitting, trying to read the whole book—“just one more.” And another: Difficult to read—force you to think—cannot glide over the words—not about “information.” We need instructions on how to read. Another living poet comes to mind. Anglican priest and singer–songwriter Malcolm Guite writes about poetry as necessary to theology, to the understanding of the Incarnation: tasting the Words, hearing the Echoes and Counterpoints, delighting in the play of Images and Allusions, Ambiguity and Ambivalence, Perspective and Paradox: “Poetry may be especially fitted as a medium for helping us apprehend something of the mystery embodied in that phrase ‘the Word was made flesh’” (Faith, Hope and Poetry: Theology and the Poetic Imagination [London, 2008], 2). In Carl’s poems, we are in the presence of the Word whom only the womb of His mother could contain. Rhymes and puns live in the gaps between sense and sound; Mary is the kenning of Christ. It is impossible to read enough in the tradition to catch all the references. All the references are in Scripture, breathed out over centuries in the liturgy. But the poems are incarnate, too. They depend on their layout on the page, on the line breaks and isolated words. Without meter or rhyme, they hold anticipation not in their sounds, but in their sense. They are incarnate, yet mute, handmaidens of spoken verse, structured in the pauses between words. This is a typographical Mary, the Mary hidden from the outside world, made visible on the page. Silent in her physicality, not to be quoted, as she remembers the day when her Son died. “X marks the spot” on the hill where the “decidedly veryUpperCase” “old Rugged Cross” stood, a marker for “latterday Pirates who / abbreviate their cache en vellum / with the selfsame Grecian phoneme” marked on the hands and feet of her Son and worn on ears, necks, breasts, and lapels, fashioned in silver and gold, “causing me to also reminisce ... / the day so long ago when Romans played / Pin the Cross on Jesus” (38). Those who have ears to hear, let them hear. The title of the book promises coverage--The Gospel According ... to Mary—and so we read the Gospel not in linear time, but in memory, Mary’s memory overlapping events from Good Friday to Christmas, the time of her memory enfolded in the time of the liturgy, the cycle of seasons turning, turning in her memory like the laundry in the washer and dryer in the opening poem. Once I surrendered to the brokenness of the lines, the soiled references to the modern world (expected, but not expected to resonate), I found myself in a mosaic of light, a medieval worshipper sitting in darkness, sunlight streaming through the glass stained by the colors of story, God’s Incarnation into Time Past, now Time Future made Time Present. Yet another marginal notation, at a place where the line break broke apart the words: “first planted His minis- / Tree in the Great / Temple Hall” (67): aslant—looking aslant through figures / glass / refractions. I cannot tell you what it was like for me to experience reading these poems, except in broken excerpts. Do we wonder to find Mary so silent in the Scriptures, she who contained in her womb the Word by which the heavens and earth were made? Take, read. You will find in these poems good wine. Rachel Fulton Brown is associate professor of History at the University of Chicago. She is author of From Judgement to Passion: Devotion to Christ and the Virgin Mary, 800–1200, and Mary and the Art of Prayer: The Hours of the Virgin in Medieval Christian Life and Thought, both published by Columbia University Press. She has co-authored and edited two books of poetry with the Dragon Common Room, her online classroom for training poets in iambic pentameter. She blogs on the internet mosaic as Fencing Bear at Prayer.

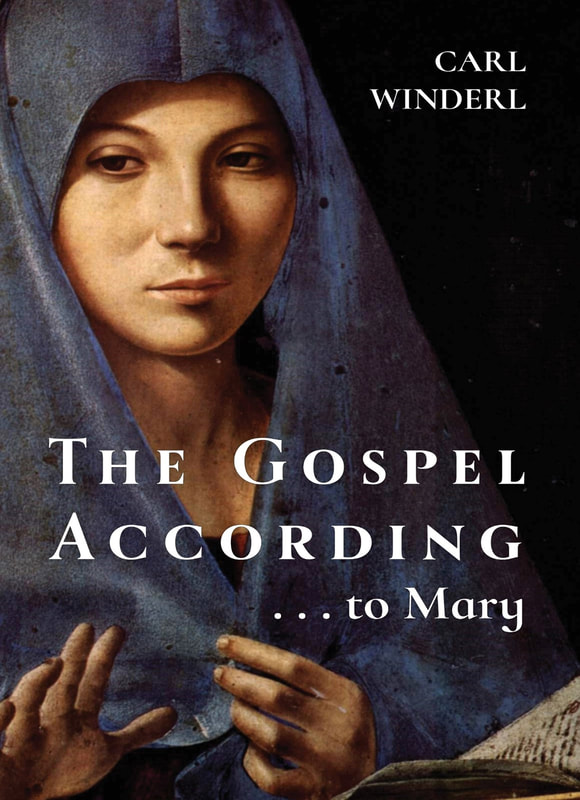

The Gospel According...to Mary by Carl Winderl Carl's work on Foreshadow: kneeling at the Manger (Poetry, December 2022) at the anti-tower (Poetry, June 2022) At Judas' funeral (Poetry, March 2022) A Writer Is Always at Work (Part 1 of 2) (Interview, May 2021) A Writer Is Always at Work (Part 2 of 2) (Interview, June 2021)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

ForecastSupport UsArchives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed